Threat Assessment: Oil and Gas Expansion Endangers Isolated Indigenous Peoples in Peru

Despite legal protections at both national and international levels, isolated Indigenous peoples live in highly vulnerable situations, in extreme danger of being pushed from their lands or killed. The expansion of extractive activities — such as oil and gas exploration and production, mining, and logging — poses a severe threat to the integrity of these reserves and to the rights and well-being of these communities.

Threat Assessment

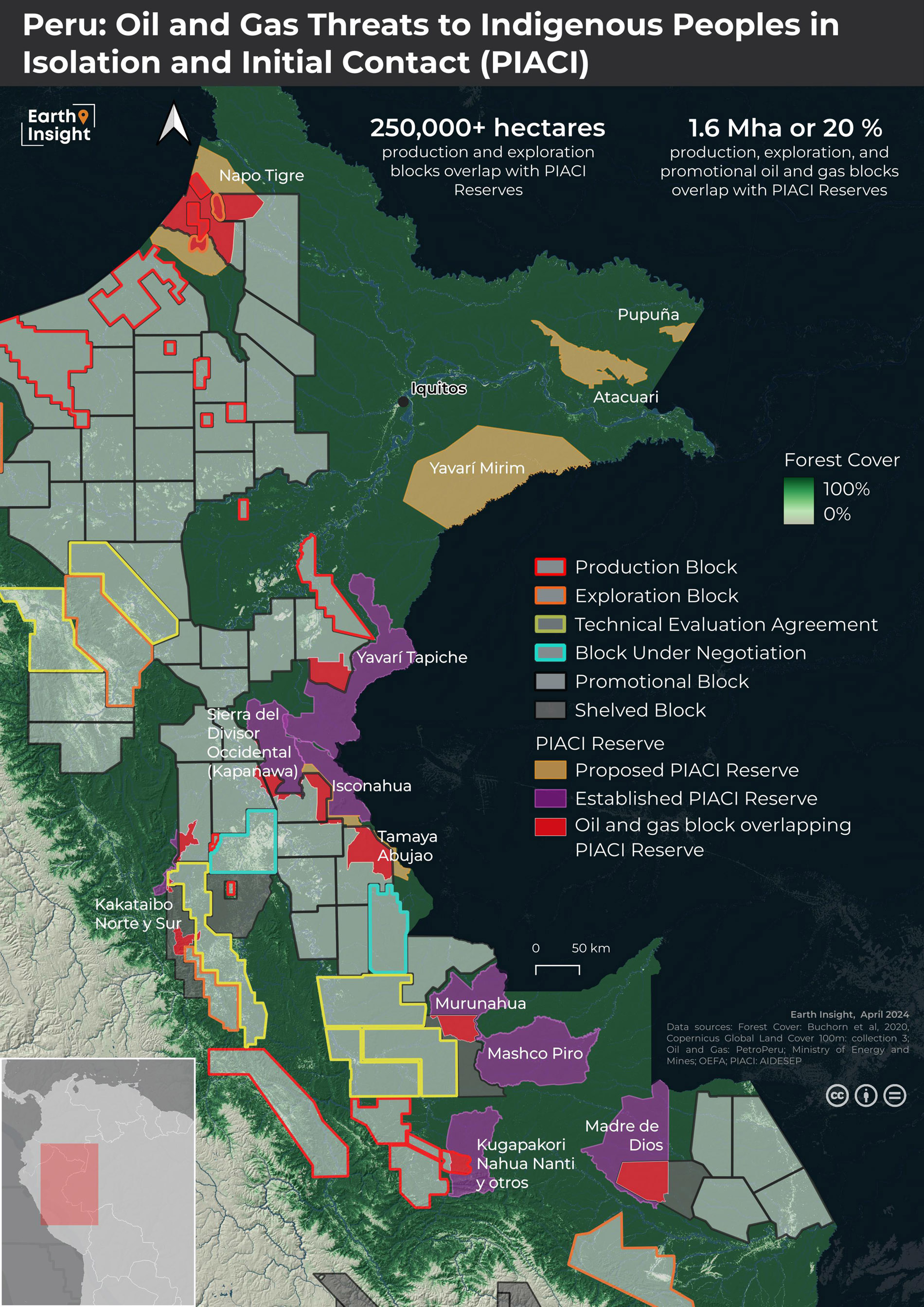

In Peru, the term "Peoples in Isolation and Initial Contact" (abbreviated as “PIACI,” the Spanish acronym) describes Indigenous peoples either living in voluntary isolation or in early stages of contact with the external world. These groups have chosen to remain isolated for historical, cultural, or personal reasons, often to protect their traditional ways of life, and avoid diseases, violence and conflicts introduced by outsiders. The Peruvian State has officially recognized the existence of at least 25 groups of Indigenous Peoples identified as PIACI who live throughout the country, including in the departments of Madre de Dios, Ucayali, Cusco, Loreto, Junín and Huánuco. According to the International Working Group for the Protection of Indigenous Peoples in Isolation and Initial Contact (abbreviated as “GTI-PIACI,” the Spanish acronym), there are also approximately 10 other PIACI groups in Peru confirmed by non-governmental organizations.

Peru's legal system — in accordance with international human rights standards and legal frameworks — protects PIACI rights and territories, creating “intangible” Indigenous Territorial Reserves in order to guarantee their fundamental rights to life and dignity. These reserves are high biodiverse places crucial to the spiritual and cultural life of these communities and integral to their survival. There are currently eight federally-recognized Indigenous Territorial Reserves and five awaiting designation in a bureaucratic creation process that can last almost thirty years, despite the PIACI Law’s legal timeframe of two to three years.

The Vice Ministers of the Environment from the Peruvian government, meet with the representatives of the Achuar, Shapra, Kukama Kukamiria, Shipibo-Conibo, Sharanahua peoples. The Apus point out the harmonious coexistence with nature and respect for their ancestral territories.

Ministerio del Ambiente (Septemeber 23, 2011 via Flickr) (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Since 2015, Indigenous federations have advocated for the recognition and protection of PIACI Territorial Corridors that cross different departments, as well as cross-border corridors with Ecuador, Colombia, Bolivia, and Brazil. For example, the Napo-Tigre Indigenous Reserve in northern Peru could connect to the Yasuní National Park and the Tagaeri Taromenane Intangible Zone (ZITT) in Ecuador to protect the cross-border PIACI territories.[vi] The Yavarí Tapiche Territorial Corridor links the Yavarí Tapiche and other Indigenous Reserves in Peru, with the Vale do Javari Indigenous Territory in Brazil, home to the largest concentration of isolated Indigenous peoples on Earth.

Despite legal protections at both national and international levels, isolated Indigenous peoples live in highly vulnerable situations, in extreme danger of being pushed from their lands or killed. The expansion of extractive activities — such as oil and gas exploration and production, mining, and logging — poses a severe threat to the integrity of these reserves and to the rights and well-being of these communities. The last ten years have seen massacres of Indigenous peoples, and some cases of first contact have caused up to 90% of community members succumbing to infections to which they have no immunity.

Last year, a legislative proposal spearheaded by the political party Fuerza Popular, the Regional Government of Loreto department (GOREL) and business associations in Loreto, would have given regional governments the power to “extinguish” all existing Indigenous reserves, as well as to decide the future of all those in the process of creation. The bill would have allowed regional governments to “annul” official recognition of the very existence of the isolated Indigenous peoples. Although the proposal, widely criticized as the 'genocide bill,' did not pass, the expansion of oil and gas exploration and other extractive activities, such as mining and logging, continues to pose significant risks to both the environment and the communities who depend on these forests.

Another proposal led by state agency PeruPetro and the Peruvian Ministry of Energy and Mines would overlay at least 31 “promotional” oil blocks on 435 Indigenous communities and multiple PIACI reserves.

These activities pose an existential threat to PIACI communities and threaten their rights to life, integrity, health, self-determination, cultural practices, and traditional livelihoods.

Tanker in the port of Talara, a refining and shipping port for Peru’s main oil-producing region.

Overflightstock via Adobe Stock

California’s rainforest oil

A report tracking the Amazon Rainforest oil supply chain found that every year California receives (on average) 50% of the crude oil extracted from the Amazonian regions of Ecuador, Colombia, and Peru. Around 11% of fuel produced for the state’s consumer market is derived from the Amazon Rainforest. One in nine tanks of jet fuel, gasoline, or diesel pumped in California is rainforest oil.

Meeting California’s high demand for Amazon oil exacts a high human cost: A study on oil exports from the Western Amazon in Ecuador, Colombia and Peru (notably the Loreto Basin) noted oil contamination wreaks irreparable harm to Indigenous communities.

The scale of impact and threats

The Peruvian Ministry of Culture estimated that there are approximately 7,500 Indigenous people living in voluntary isolation and in initial contact in and around the eight established Indigenous territorial reserves, covering more than 4 million hectares in the departments of Madre de Dios, Cuzco, Huanuco, Loreto and Ucayali. An additional five proposed reserves are in the process of creation in the departments of Loreto and Ucayali.

Oil activities have significantly impacted Indigenous territories, affecting 41 out of 65 recognized Indigenous tribes in Peru. While Peru established a process of “Previous Consultation” (not to be confused with “Free, Prior, and Informed Consent - FPIC”), Indigenous communities do not have the power to veto a project on their lands. Over the past decade, 143 cases were filed against 16 oil companies for environmental violations.

Map and analysis by Earth Insight show current and proposed oil and gas blocks overlap with 20% or 1.6 million hectares of PIACI reserves.

Expanding oil and gas risks in a “crowded forest”

Between 2000 and 2019, at least 474 oil spills occurred in the Peruvian Amazon. Although full community impact from these spills is still unknown, it has been estimated that thirty-two areas contain enough contaminated material to fill 231 national stadiums.

The expansion of oil and gas into these territories brings the risk of new oil spills and downstream effects of oil contamination. For example, Indigenous communities near oil exploration sites in the Corrientes, Pastaza, Tigre and Marañón river basins showed high levels of mercury, cadmium and lead in their bodies. Achuar communities and those living in the Corrientes and Tigre basins had the highest levels of cadmium, a known carcinogen. The growing presence of oil and gas operations, which opens the forest to activities such as illegal logging and drug trafficking, makes for “a very crowded forest,” as one researcher noted, which heightens health risks for these communities.

Indigenous people from the Indillama river community clean an oil spill close to Nayo River, Orellana province, Ecuador on July 5, 2024. An oil spill has contaminated the mighty Napo River, one of the tributaries of the Amazon, and is affecting populations, state-owned Petroecuador reported on June 27, 2024.

Bernat-Lautaro Bidegain Ros / AFP via Getty Images

Existential risks

The 2020 murders of the last family of the Mastanahua people in initial contact in the Ucayali department underscore the precarity of PIACI peoples. Plans to expand oil production heighten the existential threat to other PIACI peoples through the Peruvian Amazon. Oil exploration has already wrought severe cultural consequences in Peru: In 1984, up to 60% of a previously uncontacted Nahua tribe died from newly-introduced diseases following oil exploration and logging on their land.

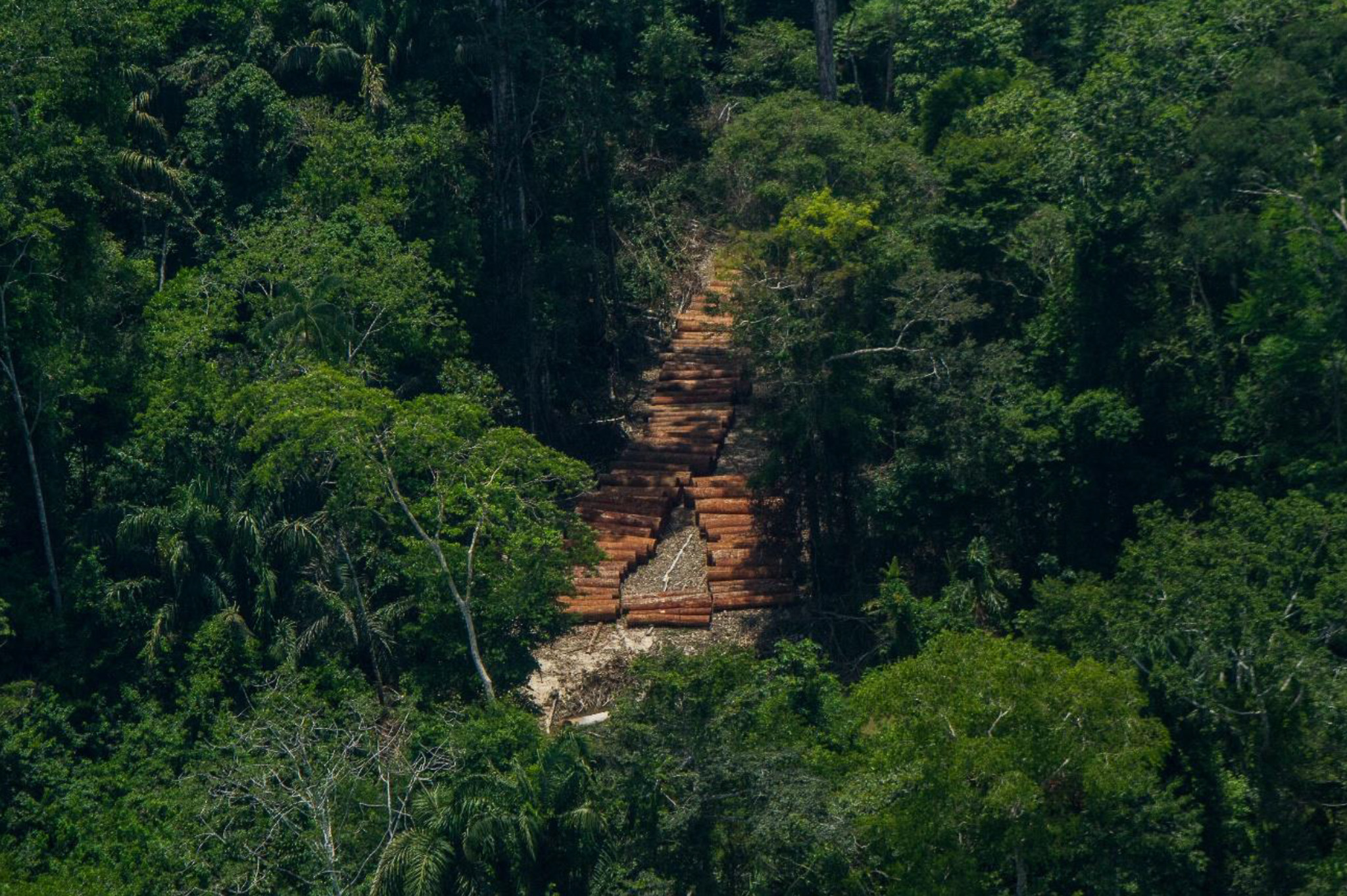

Illegal logging in the Yavarí-Tapiche, a 39.5 million-acre corridor in the Amazon rainforest that stretches from the Tapiche River in Peru to the Yavarí River in Brazil.

Courtesy of ORAU via AIDESEP

Logging also poses a grave threat to the survival of isolated Indigenous peoples. For example, in 1995 loggers in Peru forced contact with a group of the isolated Chitonahua indigenous people, shot some of them, and infected others with deadly diseases. More recently, the regional government of the Loreto department of Loreto (GOREL) in Peru awarded up to 47 logging concessions that overlap with PIACI Indigenous reserves, in violation of an express prohibition established in the Peruvian forestry law. These logging concessions cover almost 1,150 square miles of the territory of isolated Indigenous peoples, and have enabled logging in these territories over the last 8 years. The concessions still have not been annulled, in violation of Peruvian and international law.

In the Madre de Dios department of Peru, operations in logging concessions in the headwaters of the Tahuamanu and Las Piedras rivers seriously threaten the lives of one of the most numerous and well-known isolated Indigenous peoples in the world, the Mashco Piro. Logging concessions surround the PIACI reserves that are home to the Mascho Piro but which have left large areas of Mascho Piro territory unprotected. This in turn has led to conflict, as the Mascho Piro have come into contact with loggers and other actors encroaching on their forests. In 2022, a logger was shot and killed by an arrow of the Mashco Piro. According to analysis by Earth Insight, over 1 million hectares of logging concessions overlap with PIACI reserves, both established and proposed.

Oil in the headwaters

In February 2023, state energy agency PeruPetro announced it would offer 31 new oil and gas exploration areas in the Marañon, Ucayali, Salaverry, Madre de Dios and Tumbes basins. How oil activities have already affected these rivers in these regions offers a cautionary tale of what expanded operations will bring to the PIACI peoples who depend on them.

The Marañon Basin

According to the Peruvian hydrocarbon regulatory agency Osinergmin, between 1997 and 2019, more than 60 oil spills were recorded in the Marañon River, a principal tributary of the Amazon River. For decades, Kukama, Achuar, Kichwa and Quechua Indigenous peoples who live along the river have reported mysterious health problems, including fevers, headaches, diarrhea, skin rashes and miscarriages. In 2016, a Peruvian Amazon botanical specialist suggested that the impact of the oil spills could mean that communities in Loreto department’s 500-plus titled Indigenous communities would “have no fish nor land animals for food, nor fresh water to drink.”

Maranon River between Chachapoyas (Leymebamba) and Celendin.

Gerd Breitenbach via Wikipedia (CC BY 2.0)

In March 2024, an Indigenous women’s federation in Loreto won a landmark court decision that recognized the damage to the Marañón river. State oil company Petroperú was ordered to fix the leaks in the Northern Peruvian Oil Pipeline and update the 60-year-old environmental management plan for the river. The Superior Court of Justice of Loretofurther designated the plaintiffs — the women of the Huaynakana Kamatahuara Kana federation (HKK) — as ‘‘guardians of the river.” The ruling also recognized “the Marañón River and its tributaries as subjects of rights, with intrinsic value.” The decision is currently under appeal.

A month before the court ruling, PetroPeru announced a strategic operational partner for a 30-year contract to reactivate the country’s biggest oil field, Block 192, which overlaps with Achuar, Quechua and Kichwa territories in the Corrientes, Pastaza, and Tigre River basins. In response, the Peruvian Indigenous coalition AIDESEP noted that decades of oil operations had left 1,199 unrestored sites that still impact Indigenous communities. AIDESEP further charged that the new contract violated previous agreements and their right to free, prior and informed consent.

Last year, Peru began a consultation process for Lot 192’s ‘sister’ field, Lot 8, which overlaps the Corrientes and Chambira rivers and impacts the Marañón River, the Pacaya Samiria National Reserve, and the Abaníco de Pastaza wetlands, the largest Ramsar site in the Peruvian Amazon. An anthropologist from the National University of San Marcos and adviser to the platform of the Amazonian Indigenous Peoples United in Defense of their Territories (PUINAMUDT), calculated 422 oil spills and 2922 affected sites in Lots 8 and 192 alone. This year, the Peruvian state oil company signed a contract for continued extraction in Lot 8.

PetroPeru’s Board of Directors also announced this year a partner search for Lot 64, a concession Achuar and Wampis Indigenous communities in the Pastaza region have contested for violation of their right to free, prior and informed consent since 1995. Lot 64 could impact 22 communities of the Achuar, Wampis and Candoshi peoples. Oil activities would completely overlap the territories of nine communities and partially overlap with several others.

The Madre de Dios Basin

Rio Tigre waterfall in the high rainforest of Oxapampa in Pasco, Peru.

Leonid Andronov via Adobe Stock standard license.

In December 2023, officials unveiled a gas project that could rival the massive Camisea reserves. Lot 76 crosses the departments of Madre de Dios, Cusco, and Puno, and overlaps the Amarakaeri Communal Reserve, as well as the buffer zones of the world famous Bahuaja Sonene and Manu National Parks and Tambopata National Reserve. The concession also borders the territory of the Mashco Piro Indigenous peoples in voluntary isolation.

Since its creation, Lot 76 has been challenged for human rights and environmental violations. The Amarakaeri Communal Reserve was created two years before the combined oil and gas concession, which overlaps with more than 100,000 hectares of the reserve. Communities within the reserve include Harakmbut, Machiguenga and Yine Indigenous peoples. By 2009, a federation of affected communities brought legal action against Lot 76 operators for violation of their free, prior and informed consent. Next to the Amarakaeri reserve is the territory of the nomadic Mashco Piro people who are vulnerable to a multitude of existential and cultural threats from outside exposure caused by Lot 76’s reactivation.

Recommendations

To address the pressing issues facing PIACI peoples as well as primary and priority forest, we propose the following actions:

● A moratorium on all industrial activity in primary and priority forests: Safeguard critical ecosystems and Indigenous territories and rights, and allow time and space to develop appropriate financial system innovations, including adequate funding and payments for ecosystem services, debt relief, redirecting subsidies away from extractive industries, and to develop the legal mechanisms that support primary forest preservation and Indigenous co-management and restoration.

● Annul logging concessions in isolated indigenous peoples’ territories: Immediately annul the logging concessions that were awarded in the territory of isolated Indigenous peoples in Loreto, Peru.

● Support for unrecognized reserves: Extend funding and rights-based legal protection, demarcation and formal recognition to areas currently not acknowledged as PIACI reserves. This will provide the necessary legal tools to protect their lands and cultures effectively.

● Support for the protection of already created reserves: Designate adequate funding for the protection of the created Indigenous territorial reserves through monitoring and vigilance, control posts, protection agents, and the implementation of protection plans.

● Recognize and protect cross-border territorial corridors: States should establish multinational agreements at the regional level to recognize and protect territorial corridors for the free movement of PIACI peoples across national borders safeguarding their rights and protecting their traditional territories on both sides of the borders.

● Follow international conventions on the principle of ‘no contact’: National policies should adhere to recommendations by the InterAmerican Commission on Human Rights in 2013 and the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, among others.

● Guarantee the Right to Self-Determination: Uphold the right of Indigenous communities to self-determination, including the prohibition of any concessions and termination of existing licenses for natural resource exploitation within their legally recognized territories..

● Apply the Precautionary Principle: Adhere strictly to the Precautionary Principle[l] as stated in Peru’s General Environmental Law and reinforced by the Convention on Biological Diversity. Ensure that potential risks of serious or irreversible environmental damage are addressed promptly and effectively, even in the absence of full scientific certainty.

● Public Awareness and Advocacy: Increase awareness of the issues facing the PIACI Indigenous reserves through media campaigns, public engagement, and educational programs to garner broader public support for policy actions.

Additional Resources

Several recent reports underscore the global need to end oil and gas expansion – especially in Indigenous peoples’ territories and critical forest basins.

- Reports: International Working Group of Indigenous Peoples in Isolation and Initial Contact

- La Serpiente Negra de la Amazonía Peruana: El Oleoducto Norperuano

- Three Basins Threat Report: Fossil Fuel, Mining, and Industrial Expansion Threats to Forests and Communities

- Crisis Point: Oil and Gas Expansion Threats to Amazon and Congo Basin Tropical Forests and Communities

- Amazonia Against the Clock: a Regional Assessment on Where and How to Protect 80% by 2025

- Fuelling Failure: How coal, oil and gas sabotage all seventeen Sustainable Development Goals

- BankTrack’s Dodgy Deals features a Petroperú profile

- RAISG: Amazonia Under Pressure series

- The Exit Amazon Oil and Gas Platform

About AIDESEP

The Interethnic Association for the Development of the Peruvian Amazon (AIDESEP) represents Indigenous peoples of the Peruvian Amazon, defends their collective rights, and offers alternative models of development.

About COICA

The Coordination of Indigenous Organisations of the Amazon Basin (COICA) is the umbrella organization of Indigenous federations in countries in the Amazon Basin. It advocates for the rights of the 511 nationalities and groups that live in the basin – including the nearly 100 uncontacted communities.

About GTI PIACI

The International Working Group for the Protection of Indigenous Peoples in Isolation and Initial Contact, GTI-PIACI, is a collaborative initiative of 21 Indigenous and allied organizations from eight South American countries that ensures respect for the rights of Indigenous Peoples in Isolation and Initial Contact (PIACI).

About Earth Insight

Earth Insight is a research and capacity building initiative that is a sponsored project of the Resources Legacy Fund, based in Sacramento, California. Staff and partners span the globe and represent a unique grouping of individuals and organizations with diverse backgrounds in mapping and spatial analysis, communications, and policy. Earth Insight is committed to advancing new tools, awareness, and momentum for protecting critical places and supporting civil society, Indigenous peoples, and local communities in this effort.

Learn more at www.earth-insight.org

For more information please contact: Florencia Librizzi, Program Director at florencia@earth-insight.org or Edith Espejo, Program Manager at edith@earth-insight.org.

Methodology

PIACI Reserves

The PIACI reserve layer is from AIDESEP (the Interethnic Development Association of the Peruvian Amazon). An older version of the boundary of the Sierra del Divisor Occidental - Kapanawa PIACI reserve was used in this analysis because the approved boundary, following the reserve’s approval on May 22, 2024, is not currently available. The PIACI reserve layer was intersected with the oil and gas block layer to calculate the overlap of PIACI reserves with extractives.

Logging Concessions

Logging concessions were filtered out of the forest concession data from Peru’s National Forest and Wildlife Service. These logging concessions were then intersected with the PIACI reserve layer to calculate the overlap of PIACI reserves with logging.

Geospatial Data Sources

Forest Cover: C. Vancutsem, F. Achard, J.-F. Pekel, G. Vieilledent, S. Carboni, D. Simonetti, J. Gallego, L.E.O.C. Aragão, R. Nasi. Long-term (1990-2019) monitoring of forest cover changes in the humid tropics. Science Advances 2021

Oil and Gas Blocks: PetroPeru

Logging Concessions: Peru, National Forest and Wildlife Service

PIACI Reserves: The PIACI Reserves dataset is based on data compiled by AIDESEP from data available from the Peruvian Ministry of Culture and supplemented through freedom of information requests.

Populated Places: The populated places database was derived from the

Geographic Names Server maintained by the US National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency.

Geoboundaries: Runfola, D. et al. (2020) geoBoundaries: A global database of political

administrative boundaries. PLoS ONE 15(4): e0231866.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0231866

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons license CC BY-ND 4.0 DEED Attribution-NoDerivs 4.0 International. Please find a copy of this license here. If you have any queries, please address them to

info@earth-insight.org