The Independent

11/04/2025

Nick Ferris

The Democratic Republic of Congo government has opened bids for oil and gas drilling across huge swathes of the country, raising fears that the world’s last great rainforest carbon sink could be destroyed, Nick Ferris reports.

When Brazil’s President Lula chose Belém - a coastal city close to the mouth of the Amazon River - to host the UN climate conference of Cop30, he did so to ensure that the world’s largest rainforest would be both symbolically and literally at the heart of discussions.

The focus could not be more timely: the world lost an average of almost 11 million hectares - an area the size of Iceland - of forest each year over the past decade, according to the recent UN Global Forest Resources Assessment, while another recent report has found that the world is well off-track from meeting a pledge signed by more than 100 countries at Cop26 in 2021 to halt or reverse deforestation by 2030.

Things have become so bad in the Amazon that parts of the rainforest have become a net carbon source rather than a carbon sink in recent years, due to the volume of carbon produced from deforestation, cattle ranching, and agriculture outweighing the carbon absorbed by trees.

Africa’s Congo Rainforest is now the largest rainforest carbon sink in the world, absorbing around 1.5 billion tonnes of CO2, which is similar to the annual emissions of Russia. But observers fear that the Congo could go the same way as the Amazon due to development plans afoot in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, which is the vast, landlocked central-African country that contains more than half of the forest.

Earlier this year, DRC’s government opened bids for oil and gas drilling in 52 areas of the country - known in the industry as ‘oil blocks’ - which are across some 124 million hectares of the country, or more than half of the DRC landmass. Spatial mapping from the NGO Earth Insight has found that the area covered by the blocks is 64 per cent intact tropical forest - including around 72 per cent of the land encompassed by the Kivu-Kinshasa Green Corridor, which is a plan that was also announced this year aiming to create the largest protected tropical forest area in the world.

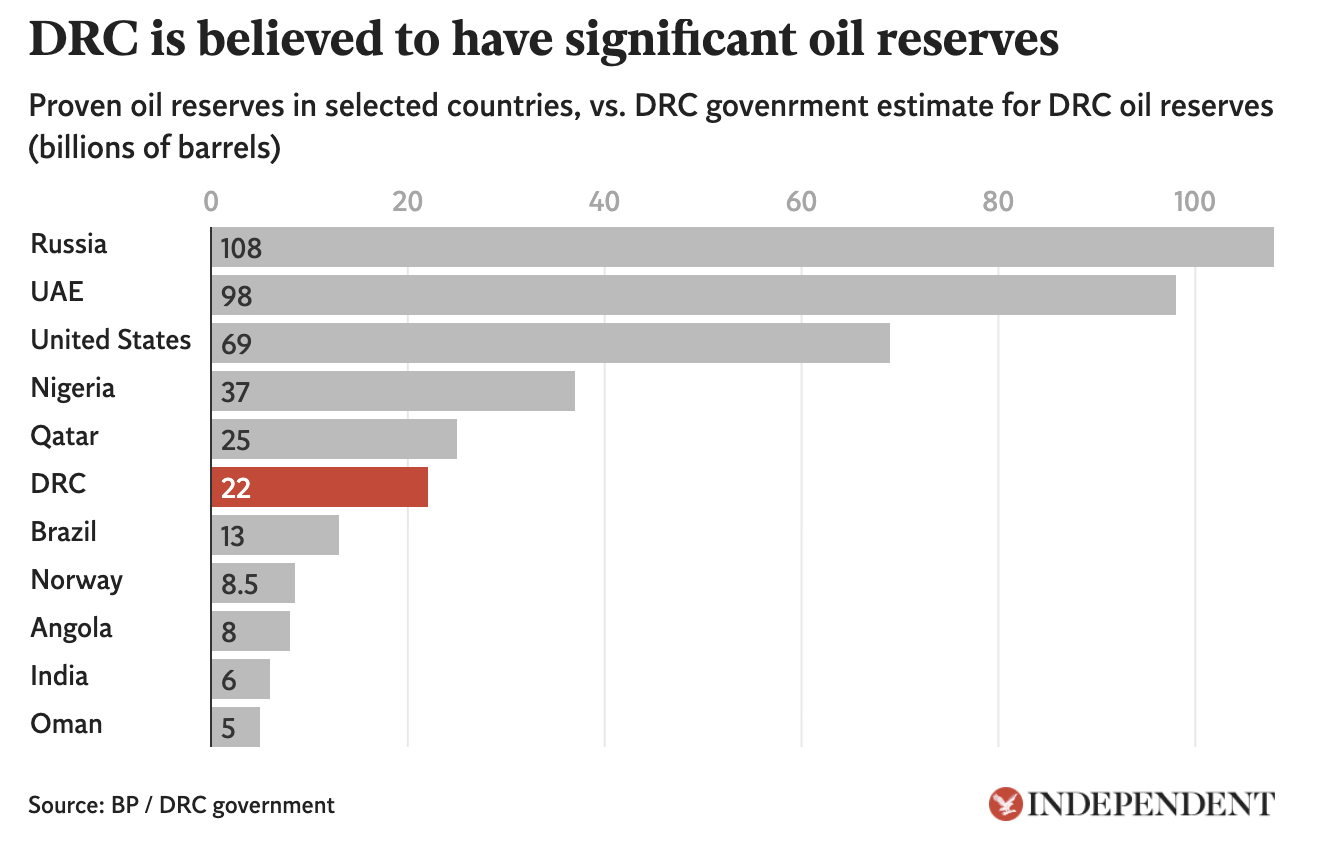

The 5-22 billion barrels of oil believed to be held in DRC represents a significant bounty - but carrying out multi-billion-dollar prospective oil investments in DRC is a daunting prospect, even for oil majors used to investing in difficult markets. The country is one of the poorest and least developed in the world, with 27 million people currently facing ‘crisis’ levels of food insecurity, a continued risk of conflict in the East, and few roads that cross from the East to the West of the country - while the reputational damage that companies would incur by drilling for oil in what is arguably the world’s last great tropical wilderness would likely be severe.

DRC previously launched an auction of oil blocks in 2022, but these were cancelled two years later after apparently not drawing significant interest.

But according to Daniel Van Dalen, a senior DRC risk analyst at the South Africa-based think tank Signal Risk, the political and economic dynamics around the current oil rights auction are far more supportive to development, raising the possibility that oil drilling really might take place in the heart of the Congo.

Proven oil reserves in selected countries, vs. DRC govenrment estimate for DRC oil reserves (billions of barrels)

The Independent

The 5-22 billion barrels of oil believed to be held in DRC represents a significant bounty - but carrying out multi-billion-dollar prospective oil investments in DRC is a daunting prospect, even for oil majors used to investing in difficult markets. The country is one of the poorest and least developed in the world, with 27 million people currently facing ‘crisis’ levels of food insecurity, a continued risk of conflict in the East, and few roads that cross from the East to the West of the country - while the reputational damage that companies would incur by drilling for oil in what is arguably the world’s last great tropical wilderness would likely be severe.

DRC previously launched an auction of oil blocks in 2022, but these were cancelled two years later after apparently not drawing significant interest.

But according to Daniel Van Dalen, a senior DRC risk analyst at the South Africa-based think tank Signal Risk, the political and economic dynamics around the current oil rights auction are far more supportive to development, raising the possibility that oil drilling really might take place in the heart of the Congo.

“During the last auction, you had a US administration that was telling DRC to not drill for these blocks - and you also had a first term Felix Tshisekedi [the DRC president] administration, which was still finding its feet,” Van Dalen explains. “Now, we have a Trump administration that obviously does not have environmental worries and is actively pushing for fossil fuel extraction - and you have a second term Tshisekedi that is reforming regulation and really pushing for investment.”

A June peace deal between the US, DRC, and Rwanda that included the US being granted rights to some of the DRC’s vast mineral rights reflects this shift in dynamic, according to Van Dalen. Meanwhile, the Chief Financial Officer of Nigerian oil firm Heirs Energies, recently told the publication Semafor said that Washington’s new pro-oil stance has resulted in banks “wanting to focus once again on upstream oil and gas financing” on the African continent.

There has already been some movement on the DRC oil blocks, after the government handed over Blocks I and II in the country’s East to the DRC state oil company Sonahydroc, which is reportedly setting up a consortium of companies to begin exploration. Minister of hydrocarbons Sakombi Molendo has said that transit for the oil would be via Uganda’s controversial East African Crude Oil Pipeline (EACOP), before the oil is exported via Tanzania's Port of Tanga.

The previous failed oil rights auction was characterised by opaque, back-room negotiations that would have put off many investors, says Van Dalen. “Now it is a totally different approach, the government feels much more technocratic, and it really seems like the adults are at the table,” he continues. “There are fewer back-channels, and a clear strategy based on two approaches: the open auction, but also a push for bilateral agreements with different partners.”

One such agreement has already been signed with Singapore-based commodities giant Trafigura - a company that has faced controversy in numerous markets where it operates. The company has signed a Memorandum of Understanding with the DRC government to help the country develop its oil assets, including around the assessment of oil reserves and the development of infrastructure.

Read Full article in the Independent