Mounting Threats: Mapping What’s at Stake as EACOP Advances

As ground breaks across Uganda and Tanzania for the East African Crude Oil Pipeline (EACOP), threats to people, biodiversity, and climate are escalating. New spatial analyses highlight how the pipeline’s advance—despite strong opposition from civil society and affected communities—intensifies risks across the region.

First proposed in 2016, EACOP has faced years of delays, resistance, and scrutiny. Yet over the past two years, construction has accelerated, with infrastructure taking shape along the pipeline’s routes and in two key oil fields: the Tilenga field, awarded to TotalEnergies, and the Kingfisher field, awarded to the Chinese company China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC).

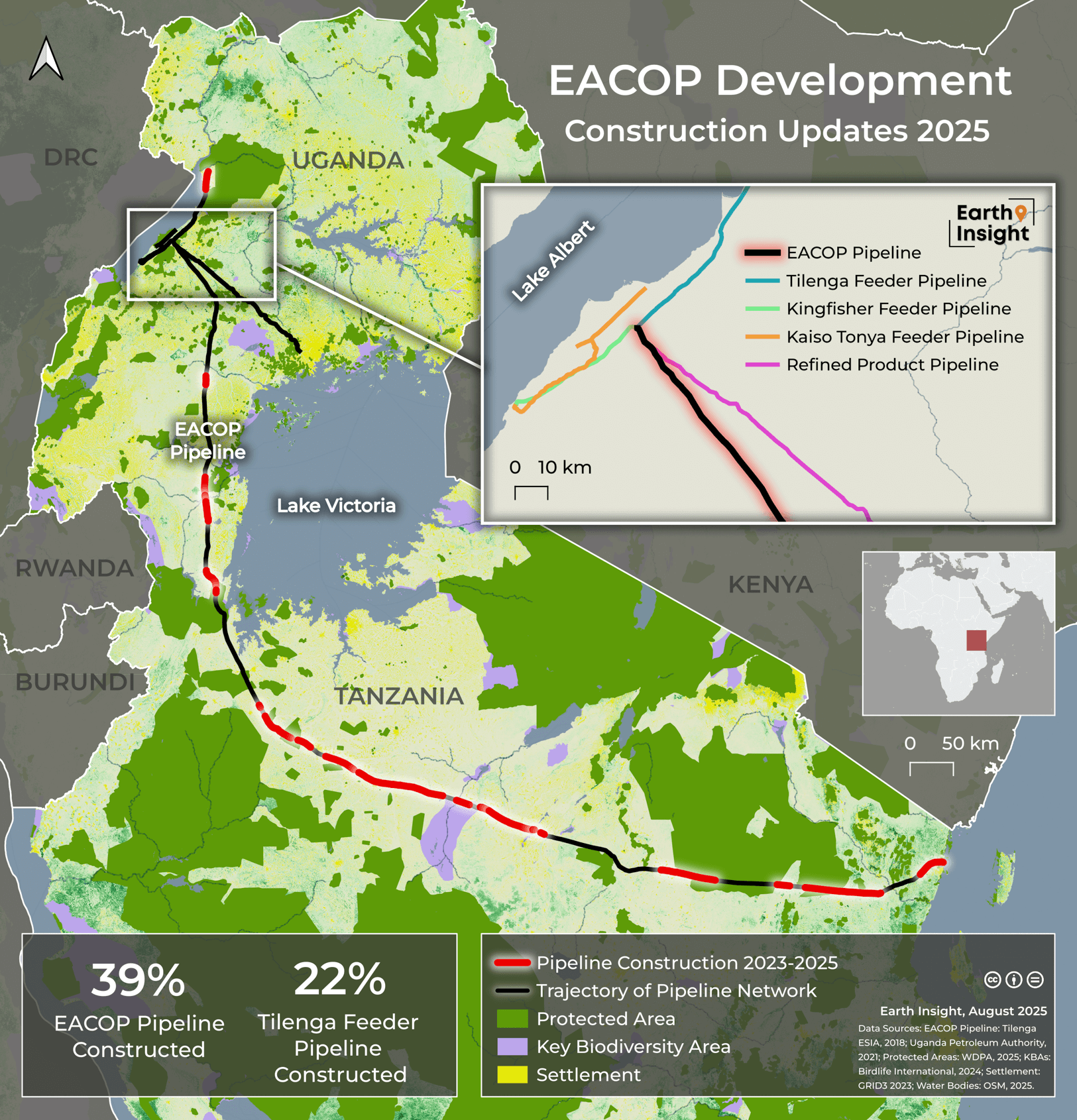

The EACOP pipeline, stretching 1,443 kilometers from Lake Albert to the port of Tanga in Tanzania, is now entering a critical phase where impacts once considered distant are becoming immediate. While some reports claim that the EACOP project is 62% complete, our analysis of satellite imagery shows that at least 39% of EACOP pipeline has now been cleared or constructed. The basis for the 62% figure is not publicly clear, underscoring the need for transparent, verifiable monitoring.

The risks are no longer hypothetical: as EACOP progresses, so too do the mounting threats it brings. This analysis highlights developments along the EACOP Project and Tilenga oil fields in Murchison Falls National Park, highlighting what is at stake if construction continues.

Rig Sinopec 1501 located at Jobi-Rii in the Murchison Falls National Park in Nwoya District, Uganda.

Image credit: Used with permission, copyright Michael Wambi / URN

Key Findings

- At least 39% of EACOP Pipeline and 22% of the Tilenga Feeder Pipeline have been cleared or constructed.

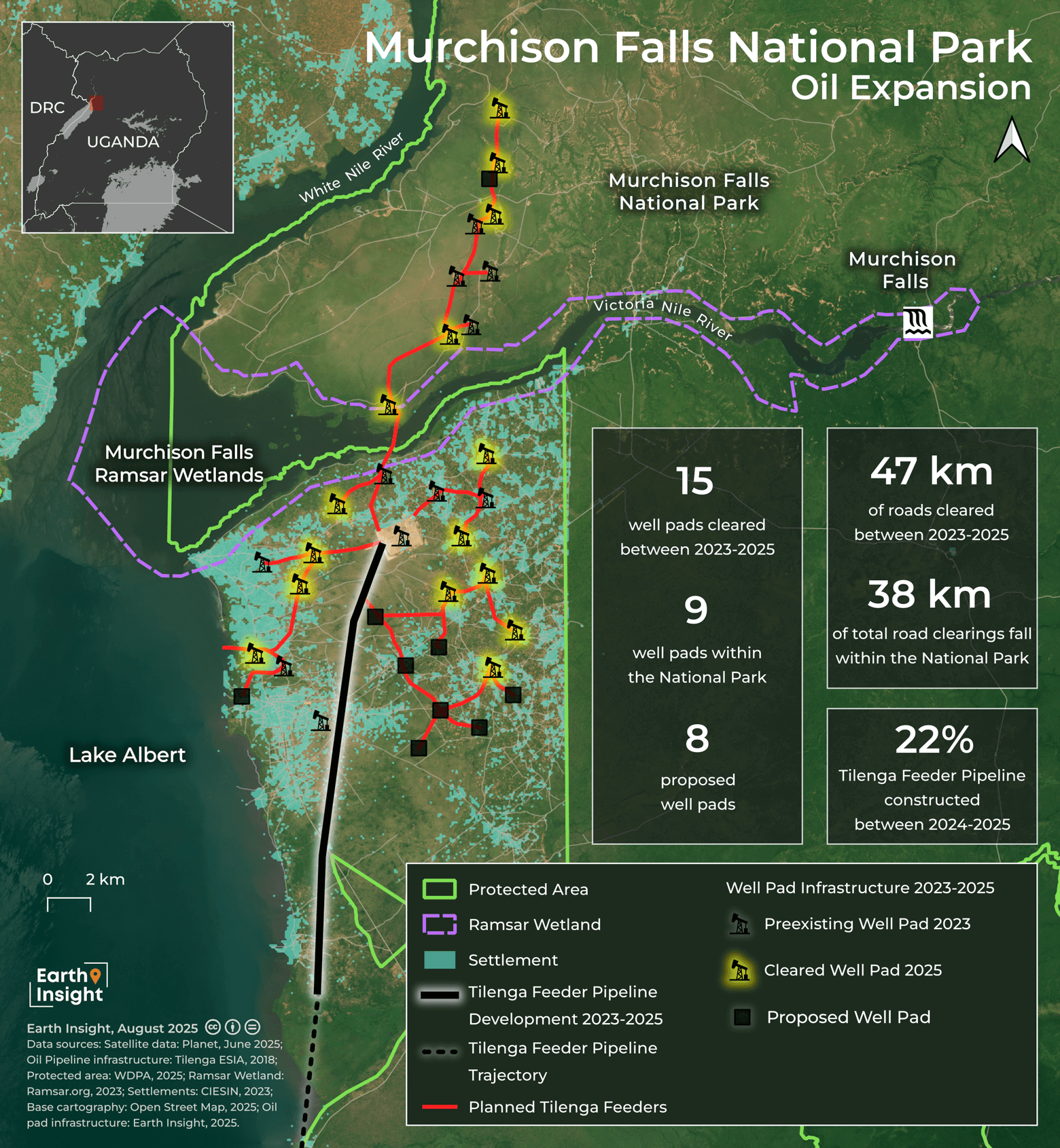

- 38km of roads and nine well pads exist within Murchison Falls National Park, Uganda’s oldest and largest national park.

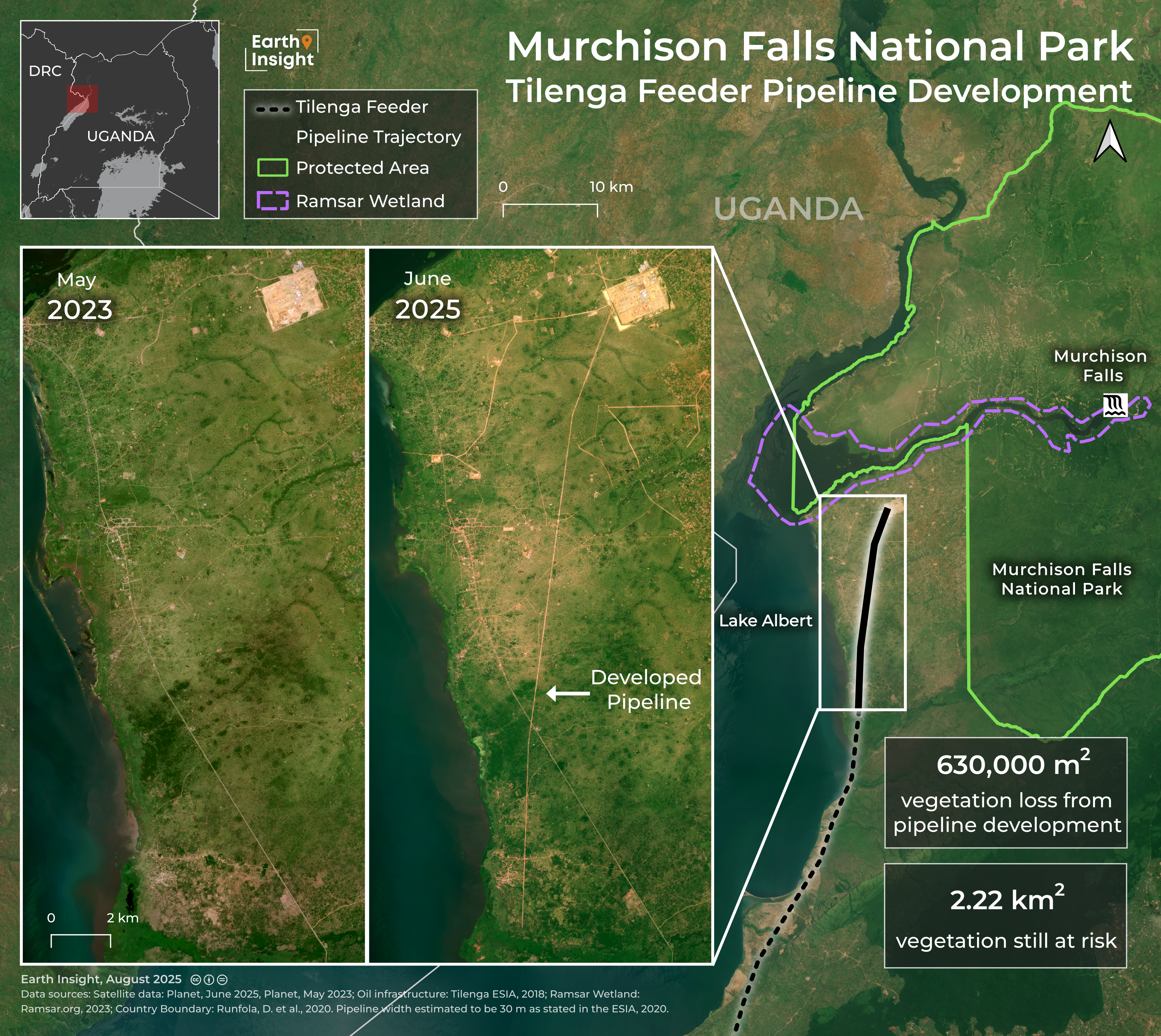

- 630,000 m2 of vegetation has been lost near Murchison Falls National Park from the development of the Tilenga Feeder Pipeline.

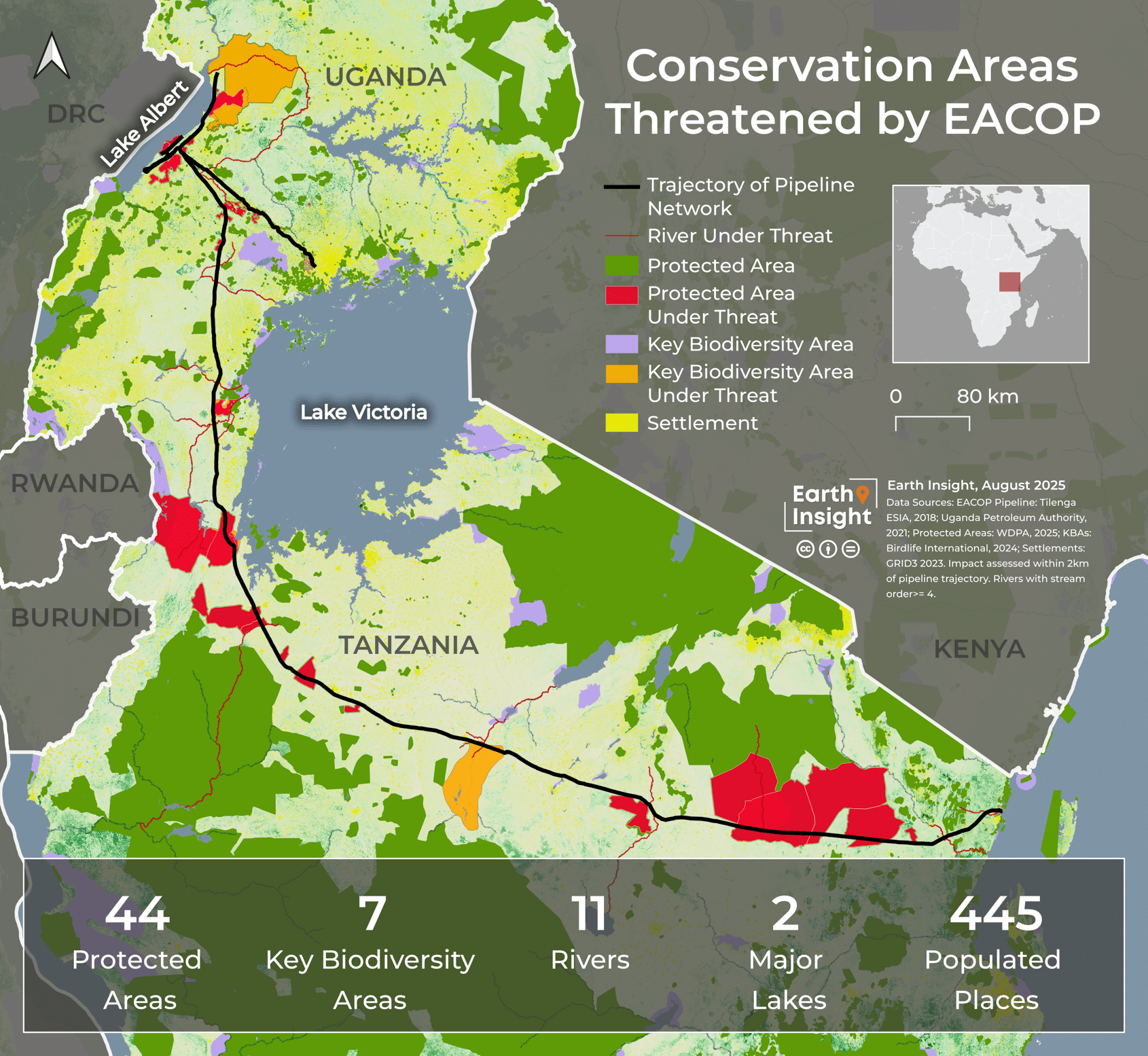

- The EACOP Project cuts through 44 protected areas and 7 Key Biodiversity Areas, threatening critical habitats, endangered species, and ecosystem services that support local communities.

Threats to Conservation Areas

New maps reveal the network of pipeline routes cut through ecologically critical areas, placing biodiversity under intense pressure and undermining global climate goals. Despite TotalEnergies’ misleading claim that the project does not cross any Ramsar zones or International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) sites, mapping shows that the EACOP Project runs through 44 protected areas registered in the World Database on Protected Areas. These include national parks, wildlife reserves, and community-managed areas that play a critical role in sustaining species, safeguarding watersheds, and supporting local livelihoods.

.png)

Murchison Falls National Park waterfall. Image credit: guided-traveller via Flickr (CC-BY-4.0)

Protected areas and Key Biodiversity Areas (KBAs) face disproportionate risks from oil spills, habitat fragmentation, noise pollution, and the wave of new infrastructure that pipelines attract. Roads, construction camps, and access routes fragment habitats further and open once-intact landscapes to poaching, logging, and agricultural encroachment. Even as developers promote ambitious biodiversity programs, the reality on the ground points to immense and escalating threats for people and nature.

Murchison Falls National Park: A Case Study in Risk

Murchison Falls National Park exemplifies what is at stake. Despite global outrage and resistance from frontline communities and environmental groups, TotalEnergies began operations at wells in the national park in 2023. New analyses reveal alarming impacts: as of June 2025, 38 kilometers of roads and nine well pads exist within Murchison Falls National park, causing significant destruction to natural resources within a legally protected area. Additional infrastructure cleared outside the park to support the Tilenga project further escalates concerns.

Murchison Falls is Uganda’s largest and oldest national park and a critical protected area for biodiversity, home to elephants, lions, hippos, and numerous endemic species. The park plays a central role in maintaining ecological balance in the region, encompassing riverine and savannah ecosystems, and serves as an important corridor for wildlife migration. Beyond its ecological value, the park is a major source of income for local communities and the country through tourism. Oil development in the park threatens both this ecological and economic lifeline, heightening socioeconomic risks and jeopardizing one of Uganda’s most iconic natural treasures.

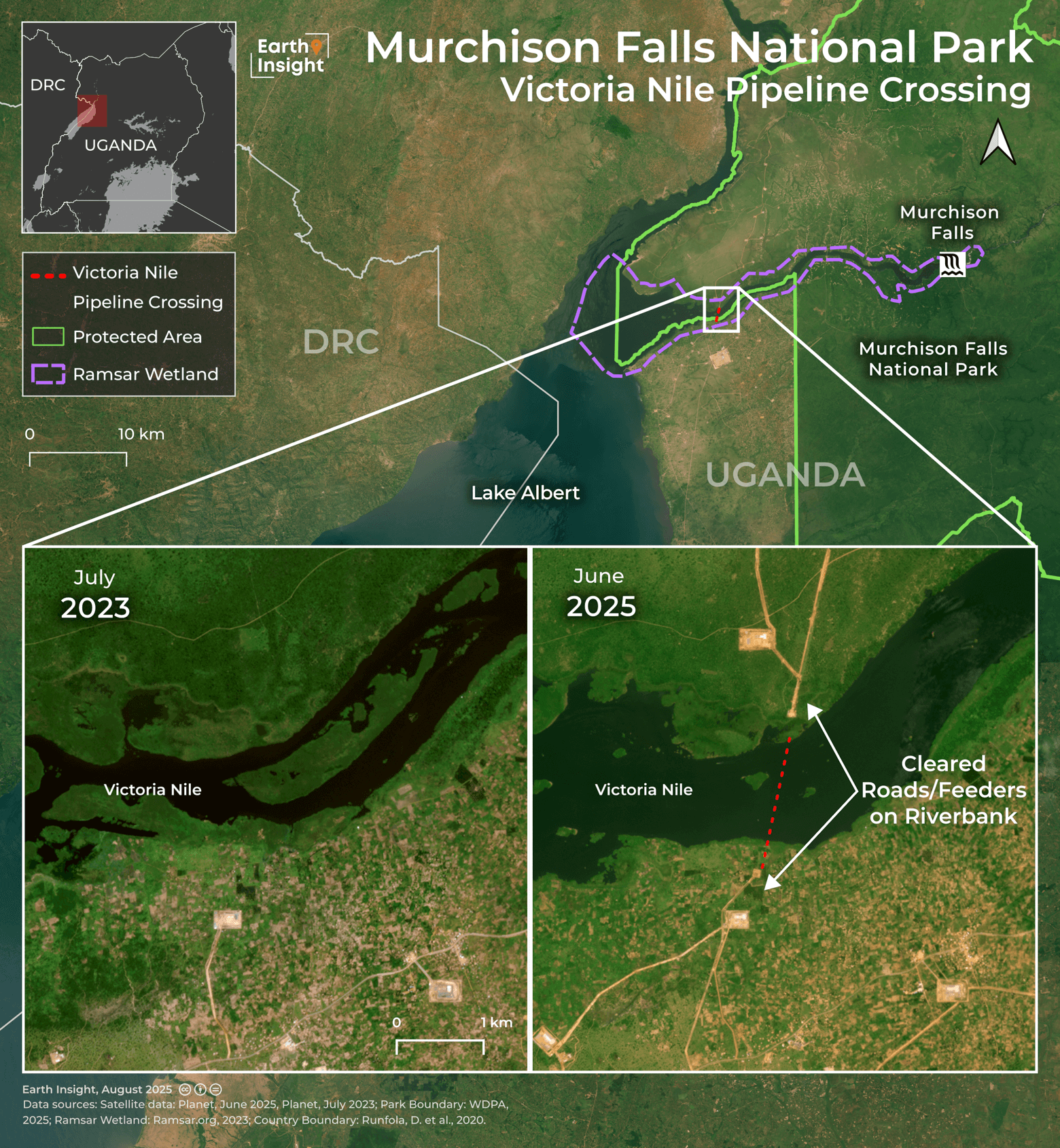

Pipeline Crossing Puts the Victoria Nile at Risk

.png)

Victoria Nile out of Lake Victoria, North of Jinja, Uganda. Image credit: Bernard Dupont via Flickr (CC BY-SA 4.0)

Satellite imagery shows roads cleared for the pipeline reaching the Victoria Nile riverbank, signaling an imminent, high-risk crossing. The Victoria Nile— flowing from Lake Victoria to Lake Albert— is a vital ecological and hydrological artery, supporting freshwater biodiversity, riparian ecosystems, and water resources for communities, agriculture, and wildlife. The site is a wetland of international importance and serves as a key spawning ground for Lake Albert’s fisheries, one of the largest in the country. A pipeline crossing here threatens oil spills, habitat disruption and increased sedimentation. Any incident here could trigger cascading impacts on wildlife, local livelihoods, and water security, compounding the threats already imposed by oil development within Murchison Falls National Park.

Livelihoods on the Line: Beyond the Numbers

Displacement caused by large-scale infrastructure projects like EACOP is not just a question of compensation, it fundamentally reshapes the lives, livelihoods, and social fabric of affected communities. A 2023 study by the Africa Institute for Energy Governance (AFIEGO) found that 41% of displaced households received low-productivity replacement land, and only 3% rated their new land as highly productive. Crop yields have declined, with 77% of households harvesting over 51 kg per season after displacement, compared to 92% before. Income losses are also significant: households earning over UGX 300,000 annually dropped from 90% to 69%, with more families forced into subsistence agriculture.

Meanwhile, Human Rights Watch reports that many displaced individuals received compensation insufficient to purchase replacement land, and delays in payments have caused further hardship. Poverty in many regions along the pipeline corridor leaves communities particularly vulnerable to coercion or inadequate compensation, forcing them to accept agreements that may not reflect their long-term well-being.

.jpg)

Meeting to inform and explain to affected community members what support they are entitled to receive after being impacted by the EACOP project. Image credit: Courtesy of AFIEGO

“The EACOP is not just displacing people from their land—it is displacing them from their dignity and future. Families who once lived off fertile soils and stable incomes are now left with barren plots, food insecurity, and deepening poverty. No amount of corporate greenwashing can hide the reality that this project could destroy lives, livelihoods, and ecosystems for generations to come.”

— Diana Nabiruma, Africa Institute for Energy Governance (AFIEGO)

Local resistance remains strong, with grassroots and community organizations advocating for fair compensation and sustainable resettlement practices. Communities have organized protests, engaged legal advocacy, and built coalitions across the pipeline corridor to ensure their voices are heard at national and international levels. These efforts highlight not only the resilience of affected households but also the potential for local actors to influence outcomes even amid powerful corporate and state interests.

EACOP: An Existential Risk to People, Nature, and Climate

As EACOP advances, the threats to biodiversity, livelihoods, and the climate grow more immediate and severe. Spatial analyses make clear that every kilometer of pipeline built carries real consequences for ecosystems, communities, and global climate targets. From Uganda’s oil fields to Tanzania’s coast, the project puts people, irreplaceable species, and critical habitats squarely in the crosshairs.

White Nile out of Lake Albert, Murchison Falls National Park, Uganda. Image credit: Bernard Dupont via Flickr (CC BY-SA 4.0)

The impacts of EACOP will also extend far beyond East Africa. When completed, it will be the world’s largest heated crude oil pipeline, generating over 34 million tons of carbon emissions annually at peak production. By enabling the extraction and export of heavy crude oil, EACOP locks East Africa into a carbon-intensive future at odds with international climate commitments. The very foundation of this project is at odds with global climate imperatives and highlights the direct link between local environmental justice and global climate action: what devastates communities and ecosystems in Uganda and Tanzania also drives the planetary climate crisis.

The evidence is unequivocal: immediate, transparent, and accountable action is essential. The demands of affected communities and others to halt the pipeline development must be respected and green economic development should be prioritised. Every delay in addressing the threats posed by EACOP amplifies irreversible harm, making the cost of inaction painfully clear.