Coral Triangle at Risk: Fossil Fuel Threats & Impacts

Download Full ReportOil and gas concessions and production areas in the Coral Triangle region overlap with tens of thousands of kilometers of marine protected areas, which include mangroves, coral reefs, and seagrass habitats, according to new analysis from Earth Insight, SkyTruth, CEED Philippines, and others.

Population growth and development needs are expected to triple energy consumption in Southeast Asia by 2050. This increased demand, combined with limited funding for renewable energies and the lack of planning for an energy transition, suggest that the region will likely fail to meet its long-term decarbonization goals, turning instead to readily available fossil fuels to address pressing needs.

What is the Coral Triangle?

Located in the tropical waters that connect the Indian and Pacific oceans, the Coral Triangle is one of the world’s most biodiverse marine regions. Extending over 10 million square kilometers (4 million square miles), this unique ecosystem spans seven countries in Southeast Asia and Melanesia: Indonesia, Malaysia, Papua New Guinea, the Philippines, Singapore, Timor-Leste and the Solomon Islands.

Its impressive marine diversity has earned the Coral Triangle the name of ‘the Amazon of the seas’. In its waters live 76% of the world’s known coral species and more than 2,000 different types of coral fish. It is a home to six of the seven marine turtle species, and acts as a feeding ground for whales and other marine mammals—including many threatened small cetaceans.

Alongside these biodiverse ecosystems live more than 120 million people who rely on the natural resources for their subsistence. The cultural diversity of these populations is equally impressive, with over 2,000 different languages present in the region. Fishing is one of the main sources of food and income for coastal communities. The Coral Triangle contains critical habitat for spawning and juvenile growth for five tuna species and is considered one of the largest tuna fisheries in the world.

This important ecosystem currently faces risks of damage or destruction from fossil fuel development. Expansion in oil, gas and liquefied natural gas (LNG) poses a growing threat to the fragile habitats and unique marine life that support many communities within the Coral Triangle.

Oil and Gas

Population growth and development needs are expected to triple energy consumption in Southeast Asia by 2050. This increased demand, combined with limited funding for renewable energies and the lack of planning for an energy transition, suggest that the region will likely fail to meet its long-term decarbonization goals, turning instead to readily available fossil fuels to address pressing needs.

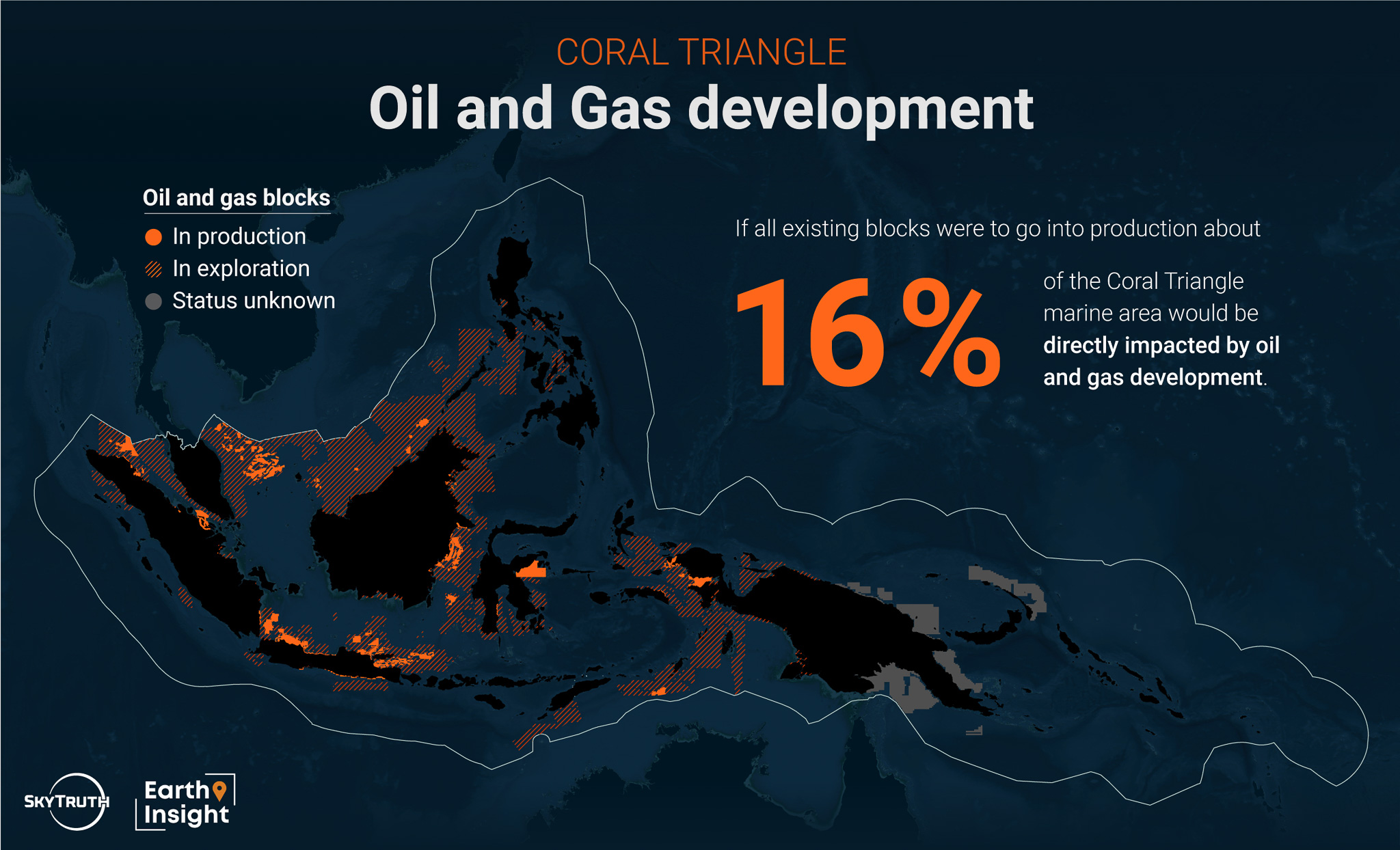

Oil and gas development in Southeast Asia is a threat to the Coral Triangle. There are over 100 known offshore oil and gas blocks that are currently producing in the region; these blocks cover more than 120,000 square kilometers of marine area–about 1% of the Coral Triangle. Looking to the future, there are more than 450 blocks that are being explored for future oil and gas extraction; these blocks cover an additional 1.6 million square kilometers. If all blocks were to go into production, about 16% of the Coral Triangle would be directly impacted by fossil fuel development. When combined, the production and exploration blocks cover an area larger than Indonesia.

An oil slick from the sunken Princess Empress Oil tanker in the Philippines.

The region has already experienced oil well leaks with consequences to marine life and the communities that depend on the environment to live and work. In 2009, the Montara oil field in the Timor Sea leaked the equivalent of 400 barrels a day for 74 days. The slick reached the Coral Triangle after a few days, destroying the livelihoods of thousands of seaweed farmers in Indonesia.

Oil pollution is also linked to vessel traffic in the area, as a product of oil tanker shipwrecks and bilge dumping. Since 2020, 793 oil slicks have been visible in the Coral Triangle in satellite imagery analyzed by SkyTruth. These slicks often trail transiting vessels which release untreated, oily wastewater in a process called bilge dumping. Of the slicks visible in the Coral Triangle, 98% were created by transiting vessels; the other 2% could be attributed to oil infrastructure. Cumulatively, all slicks covered an area over 24,000 square kilometers — nearly enough oil to cover the land in the Solomon Islands.

Liquefied Natural Gas

In recent years, countries in Southeast Asia have turned to liquefied natural gas (LNG) as an alternative to other fossil fuels. Between 2016 and 2022, Vietnam, Indonesia, the Philippines, Thailand and other countries in Southeast Asia invested more than $30 billion in LNG. As of January 2024, there are 19 LNG terminals or floating storage units operating in the Coral Triangle; Indonesia and Malaysia have the most LNG terminals with 9 and 6 respectively. There are 4 additional terminals under construction and 27 that have been proposed. Current plans in the region include doubling the amount of energy obtained from gas-fired power and increasing LNG import capacity by 80%. If LNG expansion goes ahead as planned, threats facing the region would be extensive and the Coral Triangle would end up locked in a fossil fuel economy that is incompatible with the Paris Agreement, jeopardizing the global fight against climate change.

Methane gas, the main component of LNG, is a potent greenhouse gas that contributes significantly to climate change. Although it persists in the atmosphere for shorter periods than carbon dioxide, it absorbs more energy and has a warming potential about 80 times higher than carbon dioxide over a 20-year period. Methane can enter the atmosphere from LNG-fueled ships when unburned methane leaks from the engine. The proportion of leaked methane to total methane in the fuel is termed “methane slip.” A recent report found that the most commonly used LNG engine has an average methane slip of 6.4%, nearly double the values assumed by the EU and the International Maritime Organization. LNG carriers can also emit major plumes of methane at port when loading or unloading LNG cargo. The emission rate of methane plumes is estimated to be even greater than the rate of methane slip from LNG-fueled vessels.

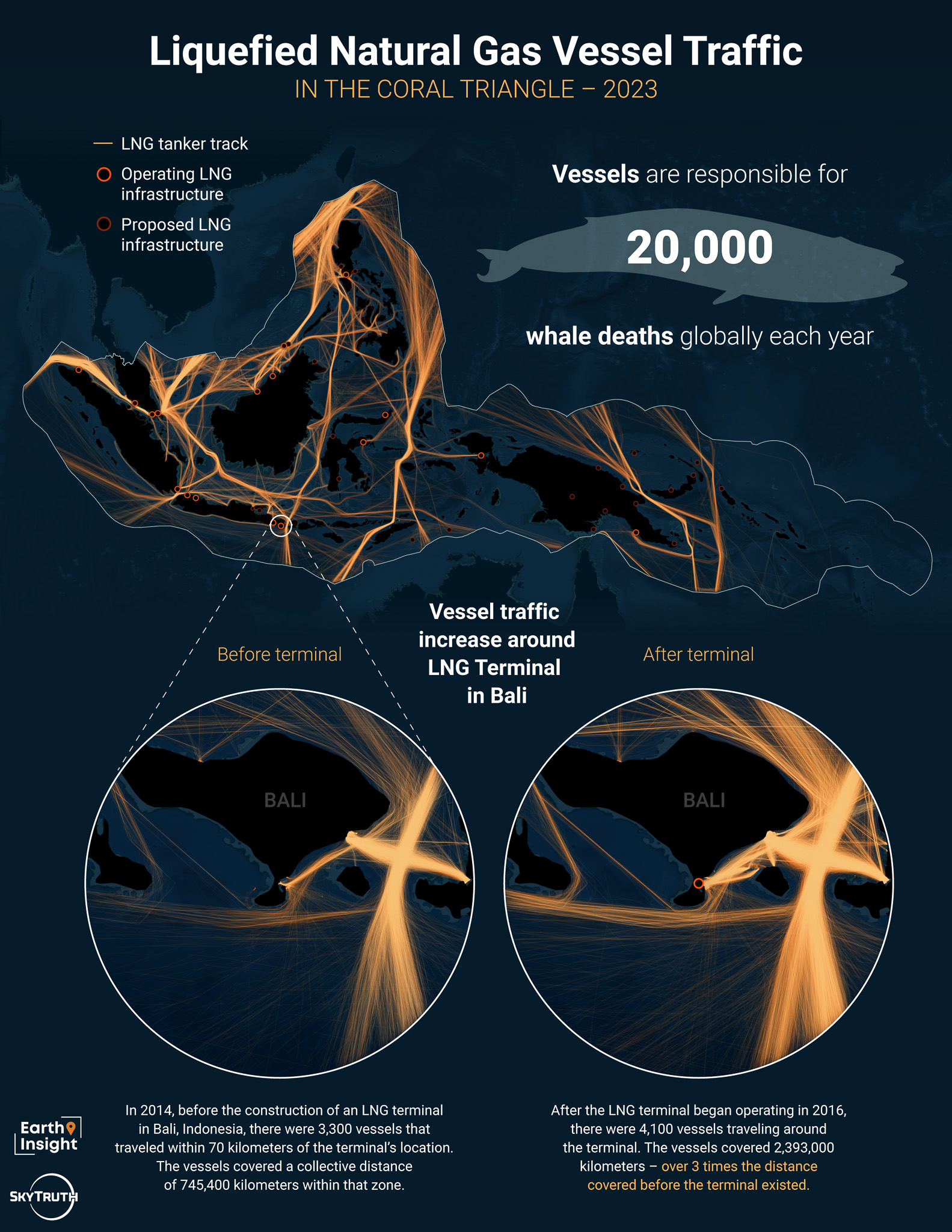

To execute the planned degree of LNG development, several terminals would need to be built in environmentally sensitive areas. In these areas, the risk of harm from construction—including air and water pollution caused by vessel and truck activity—is greatly increased. LNG expansion would also result in greater vessel traffic in the region, increasing the risk of ship collisions with marine animals and the introduction of invasive species to sensitive habitats. Vessels are responsible for 20,000 whale deaths every year, according to the NGO World Sustainability Organization. The rise in shipping traffic is a major driver behind the spread of invasive species, which ranks among the top threats to marine ecosystems and biodiversity. The planned development would increase marine traffic around the Verde Island Passage, one of the most biodiverse places in the Coral Triangle.

Threats to Critical Habitats

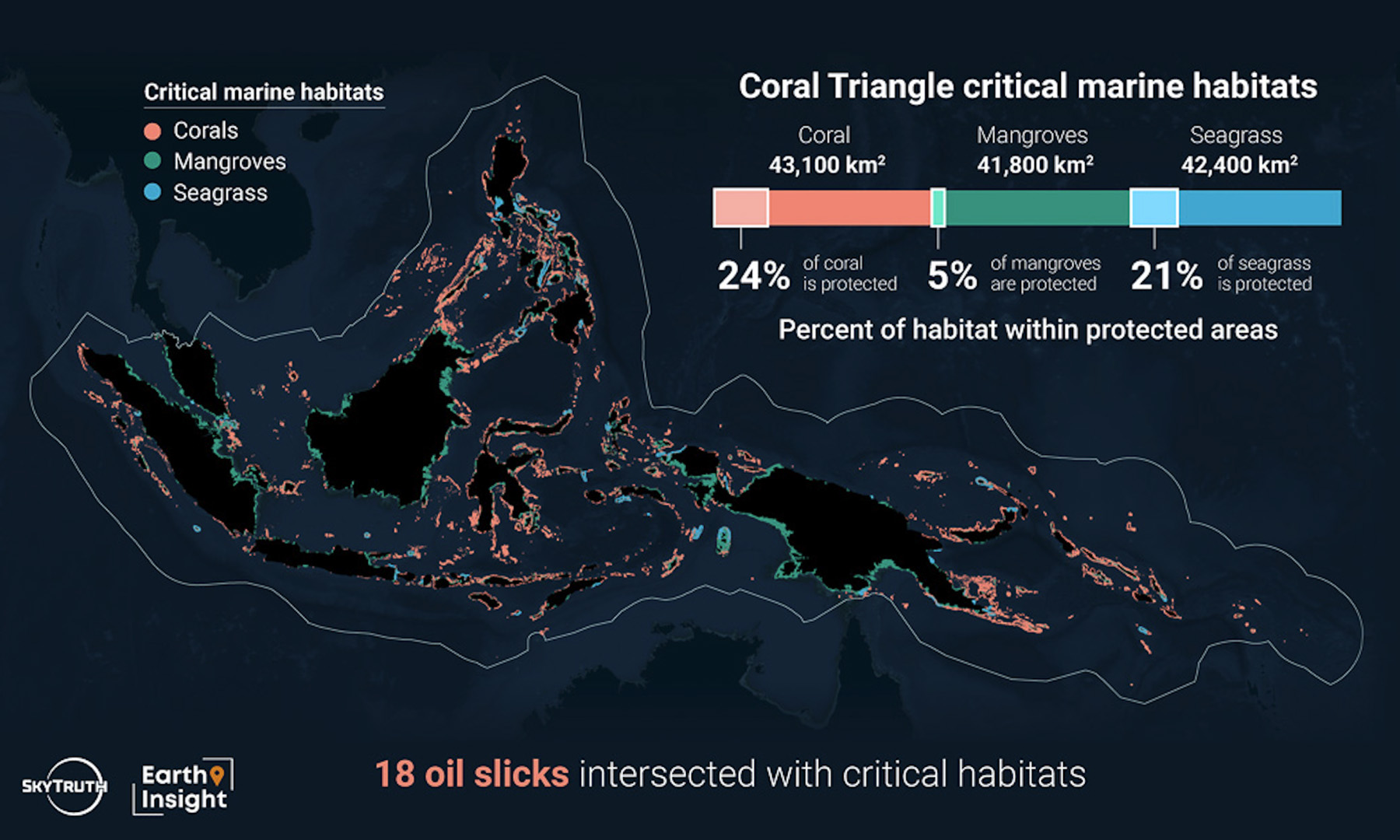

The combination of threats outlined in the previous sections imperils the delicate and essential ecosystems in the Coral Triangle. Coral reefs, mangroves and seagrass play a critical role in protecting coastal areas from floods, supporting fish populations and attracting tourism in the Coral Triangle. Additionally, these habitats improve water quality and act as carbon sinks in the fight against climate change. According to an estimate from the Asian Development Bank, economic losses due to climate change alone amount to almost $38.3 billion, with degradation of coral reefs and mangroves as the main causes.

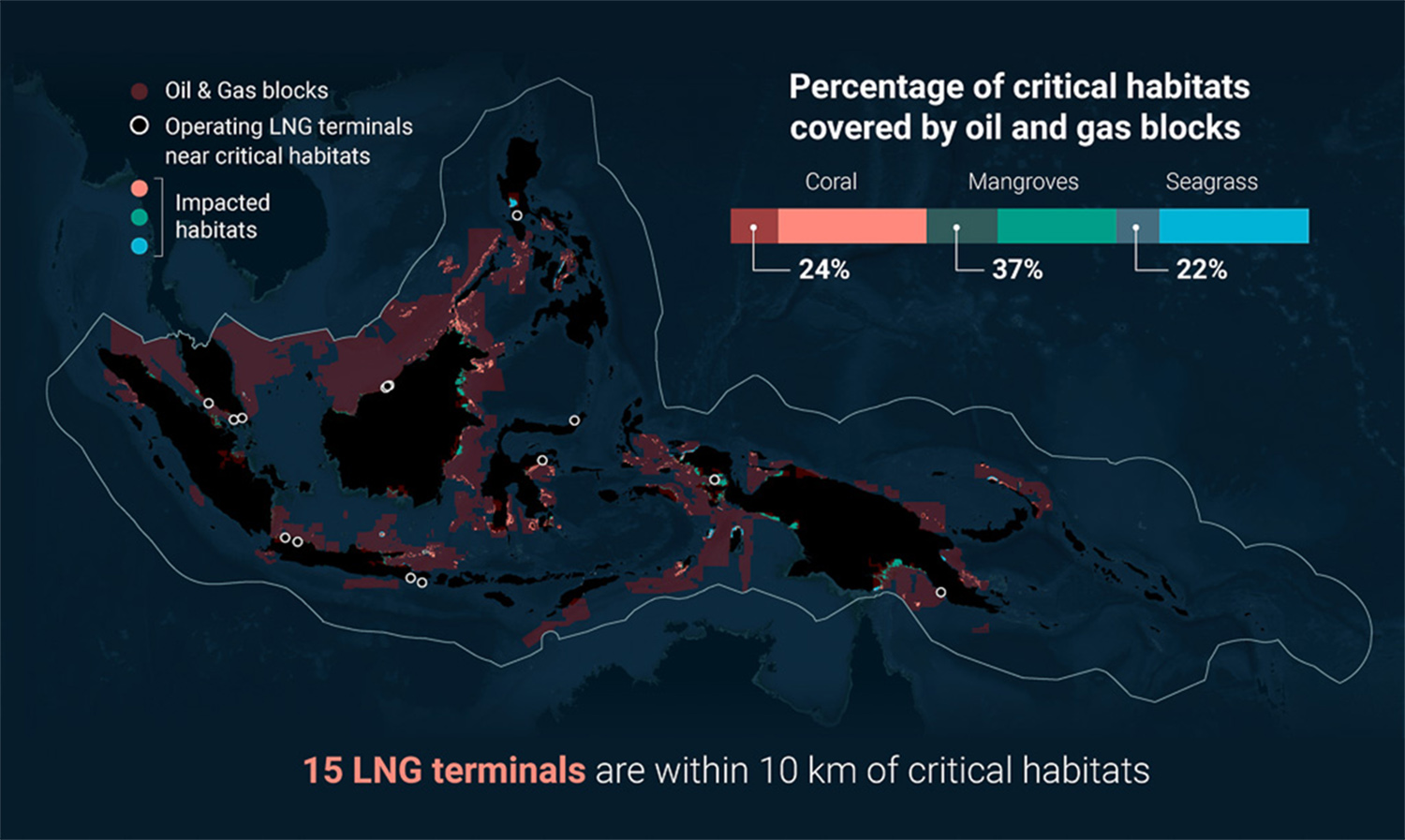

In the Coral Triangle, oil and gas blocks cover 24% of coral habitats, 22% of seagrass habitats, and 37% of mangrove habitats. Additionally, 18 oil slicks intersected with coral or seagrass habitats since 2020. As exemplified by the Princess Empress oil spill which impacted more than 50 square kilometers of coral, mangrove and seagrass habitats, accidents involving oil tankers can also have wide reaching effects on the environment.

Oil can result in serious damage to coastal ecosystems, including permanent habitat loss, decreased local biodiversity, and eroded beaches. Oil-contaminated sediment can remain on the shoreline for long periods, affecting shore birds, and oil in the water column can injure fish, marine mammals, and filter feeders like coral. It can also make fish unsafe to consume, leaving coastal communities unable to rely on a life-sustaining food source.

The first Chinese built LNG vessel being delivered from Hudong Zhunghao to China LNG Shipping. Image credit: Hereward L via Flickr (CC BY 4.0 DEED)

Shipping, as well as exploration and drilling in oil and gas blocks, creates noise pollution that can also have harmful effects on marine life. Many marine species rely on sound for essential daily activities – such as communicating, locating food, avoiding predators, reproducing, and navigating. Seismic guns used for offshore exploration generate one of the loudest man-made sounds in the ocean. Commercial shipping is also recognized as one of the primary sources of underwater noise. These man-made noises can mask or mimic animal sounds, which can alter critical behaviors, displace fish and whales, damage animals’ hearing and kill zooplankton – an important element of the marine food chain.

The increased infrastructure and vessel traffic that accompanies LNG expansion also poses a threat to the Coral Triangle’s marine and coastal ecosystems. Of the 19 operational LNG terminals in the Coral Triangle, 15 are within 10 kilometers of coral, seagrass or mangrove habitats. In addition, 17 of the 31 proposed or under-construction terminals fall within 10 kilometers of these sensitive habitats. With more vessel traffic, marine pollution and environmental disruption will likely increase. Antifouling agents that prevent the growth of organisms on vessel hulls contain compounds that can damage the environment. These antifouling agents, which can persist in water and sediment, have a wide range of negative effects on fish, shellfish and marine mammals. Wastewater discharge from ships is also a concern, as it can contain harmful pathogens, organic matter and chemical residues. In the worst cases, untreated wastewater discharge has led to toxic algal blooms, oxygen depletion of the ocean, the spread of bacteria and viruses, and the contamination of fish and seafood.

Threats to Conservation Areas

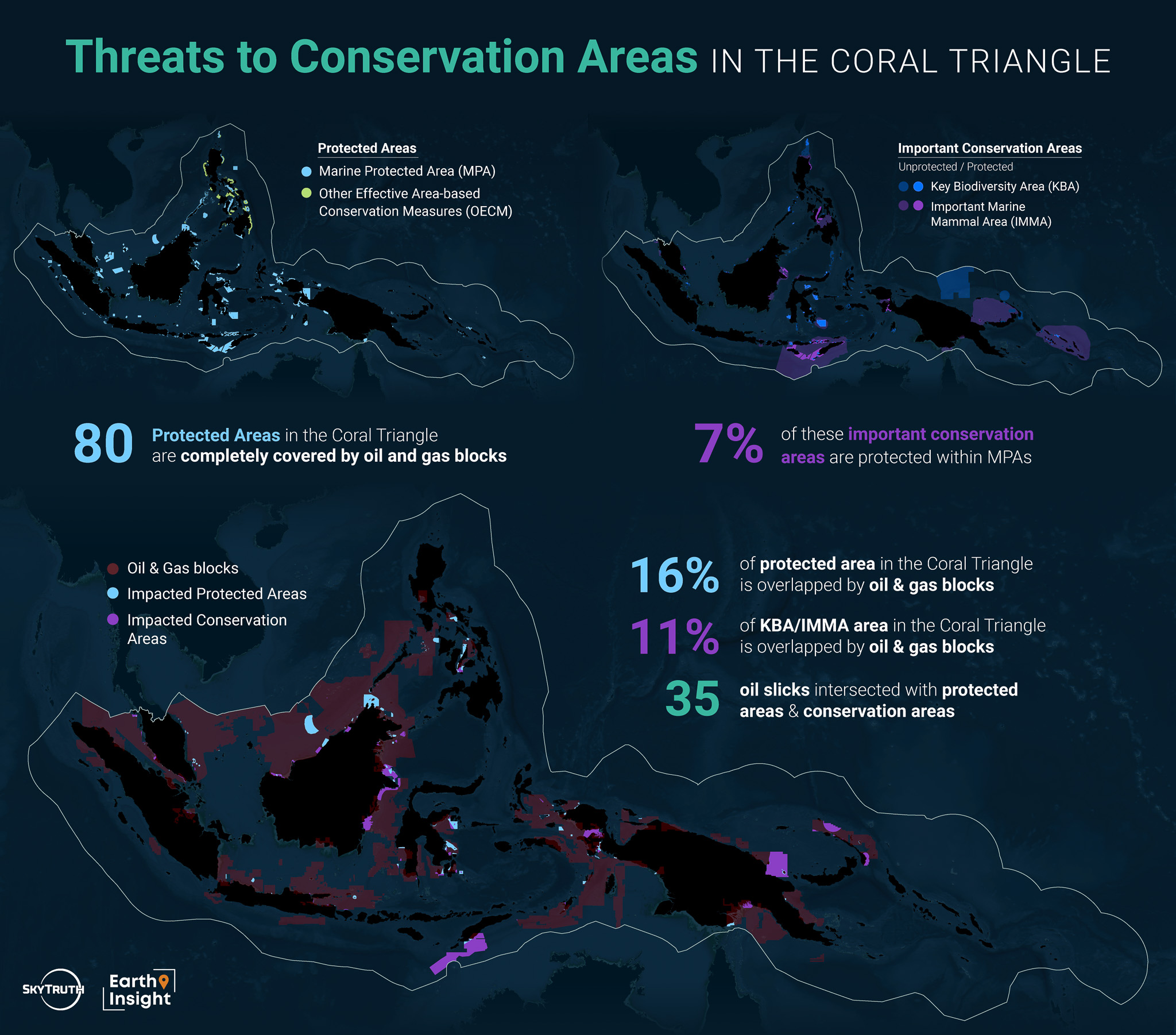

The Coral Triangle contains more than 600 Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) and 30 other effective area-based conservation measure (OECM) areas. An MPA is regulated and managed to achieve specific conservation objectives, while an OECM is managed to achieve long-term outcomes for the conservation of biodiversity according to cultural, spiritual, socio-economic, and other locally relevant values. The large majority of these conservation areas are designated by countries within the Coral Triangle and the responsibility for their protection generally falls to national or subnational agencies. Most of the MPAs in the Coral Triangle have not been assessed for their protection level. However, the MPAtlas has assessed 24 MPAs and found 10 have some level of protection, while 14 are still in a proposed stage.

A lack of protection within MPAs in the Coral Triangle is evident from the degree of overlap between these areas and oil and gas infrastructure, pollution and vessel traffic. About 16% of MPA area in the Coral Triangle overlaps with oil and gas blocks - a large majority of which are still in the exploration phase. There are 80 MPAs in the Coral Triangle that are completely covered by oil and gas blocks - 55 of which are found in Malaysian waters. Additionally, 35 oil slicks appeared within MPA boundaries. The most oil-impacted MPAs are located in highly trafficked areas of Indonesian or Malaysian waters. LNG vessels also pass through many of these managed spaces. In 2023, the three MPAs with the greatest amount of LNG vessel traffic were all large MPAs in Indonesian waters. Two of these areas experienced more than 100 transits.

%20Malaysia.jpg)

Green turtle (Chelonia mydas) in Pulau Sipadan, Sabah, Malaysia. Image credit: Bernard Dupont via Flickr (CC BY-SA 2.0 DEED)

Spatially, only about 2.5% of marine area in the Coral Triangle is protected within MPAs - 300,000 km2 out of 12 million km2. Many ecologically important habitats fall outside of currently protected areas. Key Biodiversity Areas (KBA) and Important Marine Mammal Areas (IMMA) are two distinctions used by conservation organizations to identify portions of habitat that could be protected based on the importance of their biodiversity or the support they provide for marine mammal populations. In the Coral Triangle, only 7% of these KBAs and IMMAs are protected within MPAs. Without the protection afforded by MPAs, these important spaces are subject to a higher quantity of threats from fossil fuel development and pollution. Of these key conservation areas, 11% is covered by oil and gas blocks, and the majority of that overlap occurs in unprotected sections. There are also 35 oil slicks that overlap with KBA and IMMA areas, 33 of which are in unprotected portions.

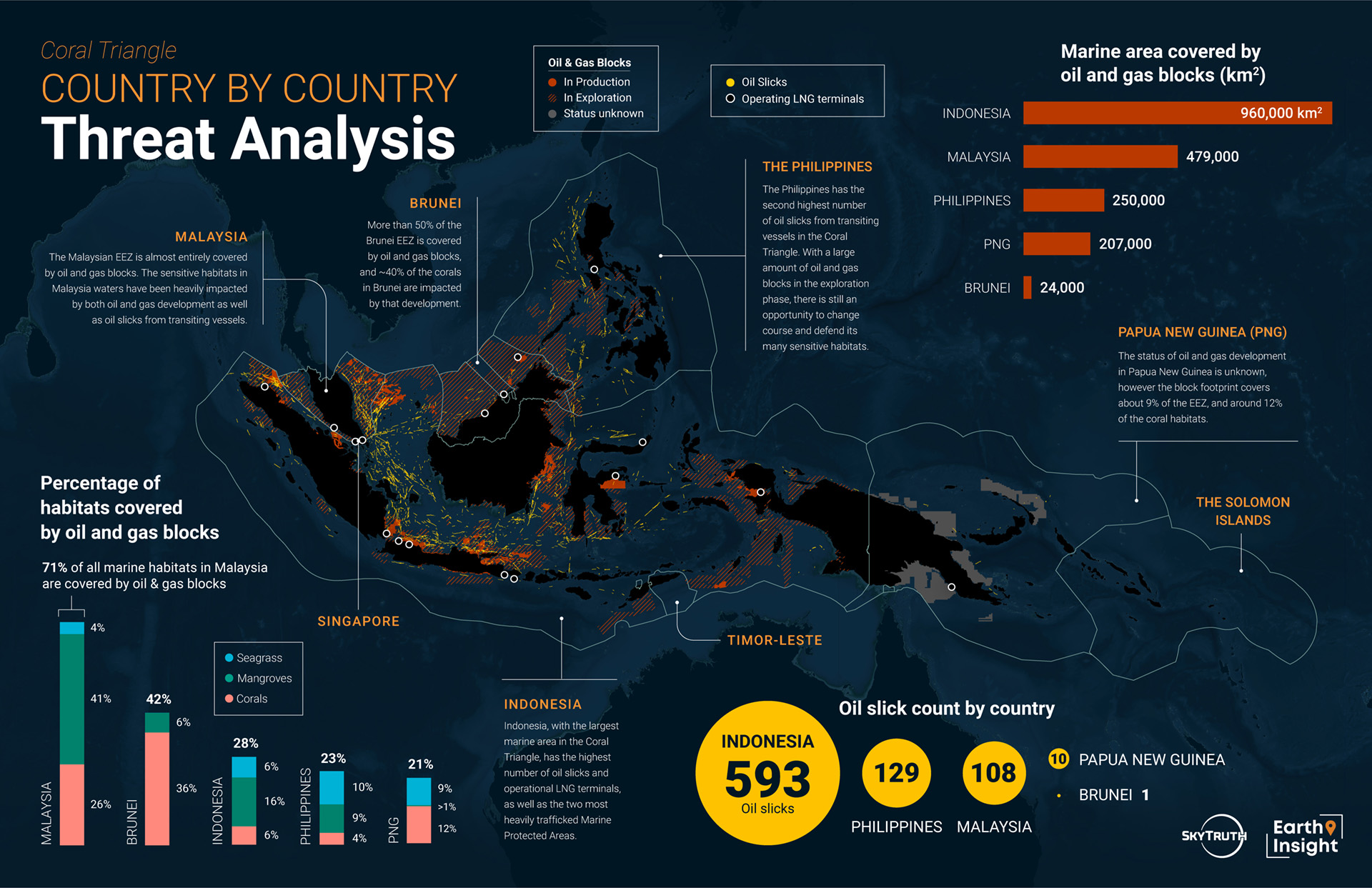

Country by Country Threat Analysis

Threats to Communities in the Coral Triangle

Oil and gas exploration takes a toll on the people who call the Coral Triangle home, beyond the impacts to their environment. Oil spills not only damage marine habitats but also affect a population's mental and physical health, education, tourism, culture, and recreation. After the 2023 Princess Empress oil spill in the Philippines, people in local communities reported experiencing illness including nausea and dizziness. The spill forced the suspension of classes in some schools as a result of fumes from oil-laden shorelines, and left many fisherfolk out of work for extended periods of time.

Ecotourism - a source of sustainable revenue for many countries in the Coral Triangle - also suffers as a result of fossil fuel development and pollution. In response to a 2006 oil spill in the Philippines, it was estimated that the tourism sector lost around 650 million Philippine pesos ($11.6 million USD) in income. The construction of new terminals and increased marine traffic can also disrupt small-scale fishing and affect ecotourism - an industry on which tens of thousands people rely.

The Philippine Coast Guard distributed relief packs containing food and supplies to fisherfolk who could not work during the Princess Empress oil spill.

In addition to the macroeconomic impacts, expanding fossil fuel infrastructure has a disproportionate effect on local populations and Indigenous communities. In South Bali, Indonesia, the construction of an LNG terminal in the port of Benoa threatens six temples of Indigenous Intaran communities. An Intaran leader stated that the terminal would “infringe on sacred temple grounds.” Locals are worried that the terminal will negatively affect the Sanur Beach community, a highly populated area, and the surrounding environment alike through coastline erosion and damage to a mangrove forest.

Investment in fossil fuels also has long-term economic consequences for the countries where these resources are located. Countries with large fossil fuel reserves are often locked in a debt trap: they borrow money to exploit the resources, but end up spending a large share of the revenue servicing the debt. A recent report by the Overseas Development Institute showed that between 2010 and 2020, most fossil fuel exporting countries saw an increase in government debt relative to the size of their economies. Countries in the Coral Triangle are no strangers to this situation.

Community-Drive Responses

Across the Coral Triangle, local communities are organizing resistance movements to oppose oil and gas projects in the region. In the Philippines, a coalition of civil organizations called Protect VIP has been leading the actions against fossil fuel expansion in the Verde Island Passage. In November 2022, they submitted a letter to Shell expressing their opposition to the company’s plans for a new LNG terminal in Batangas. In the letter they noted that the new facility would disrupt small-scale fishing, negatively impact ecotourism, and boost marine traffic in the region – increasing the risk of oil spills and improper waste disposal.

Since the Princess Empress oil spill, citizen-led initiatives like Bantay Oil Spill have sought accountability and action in response to the disaster and have worked to prevent future spills. The group works to increase transparency around oil spills by sharing reports, images and updates with affected communities.

Environmental and social groups protest the expansion of a coal power plant in front of the building in Calaca, Batangas, Philippines.

Photo credit: Aileen Dimatatac/Break Free 2016.

In Indonesia, there is also growing opposition to LNG development plans near Bali. Indigenous communities, environmental organizations and civil society groups submitted a letter of rejection against the construction of an LNG terminal in Sidakarya. The group argued that the terminal would destroy a mangrove forest, damage coral reefs, and infringe upon six temples in an indigenous village.

On a regional scale, the Coral Triangle Initiative was established in 2009 as a multinational partnership between Indonesia, Malaysia, Papua New Guinea, the Philippines, the Solomon Islands and Timor-Leste to address critical issues facing the area. The initiative focuses on addressing food security, impacts of climate change and protecting marine biodiversity in its effort to strengthen the Coral Triangle’s resilience to threats.

Recommendations

While all of the local and regional efforts to combat threats facing the Coral Triangle are moving the needle in the right direction, more needs to be done by regional and international decision-makers and financial institutions to protect this vital and diverse region. Here are some of the solutions that could help ensure the preservation of biodiversity and communities within the Coral Triangle:

- Enact and uphold a moratorium on oil and gas development and other industrial activities in all vulnerable habitats in the Coral Triangle, ensuring that no new exploration or extraction takes place, while phasing out existing fossil fuel operations.

- Leapfrog the use of LNG as a transition fuel and develop renewable energy plans aligned with the 1.5°C Paris temperature goal that allow for a clean, sustainable energy transition and prevent carbon lock-in from fossil fuels. Over 99% of solar and wind potential in Southeast Asia remains untapped.

- Increase funding for biodiversity protection, ensuring higher levels of enforcement within these areas and expanding the network of protected areas to include more sensitive habitats.

- Create and implement National Adaptation Plans to pursue Loss and Damage resources through international financial mechanisms. These funds were created to make industrialized economies pay their dues to countries suffering the worst consequences of climate change.

- Prevent the industrialization of coastlines along the Coral Triangle to limit the impacts to ecosystems and the ways of life of local populations, while supporting the livelihoods and cultural ways of fisherfolks and coastal communities.

- Designate the Coral Triangle a Particularly Sensitive Sea Area – a classification provided by the International Maritime Organization (IMO) that provides a region with special protection from maritime activities because of ecological, socio-economic, and cultural significance.