Forests to Frontlines: Oil Expansion Threats in the DRC

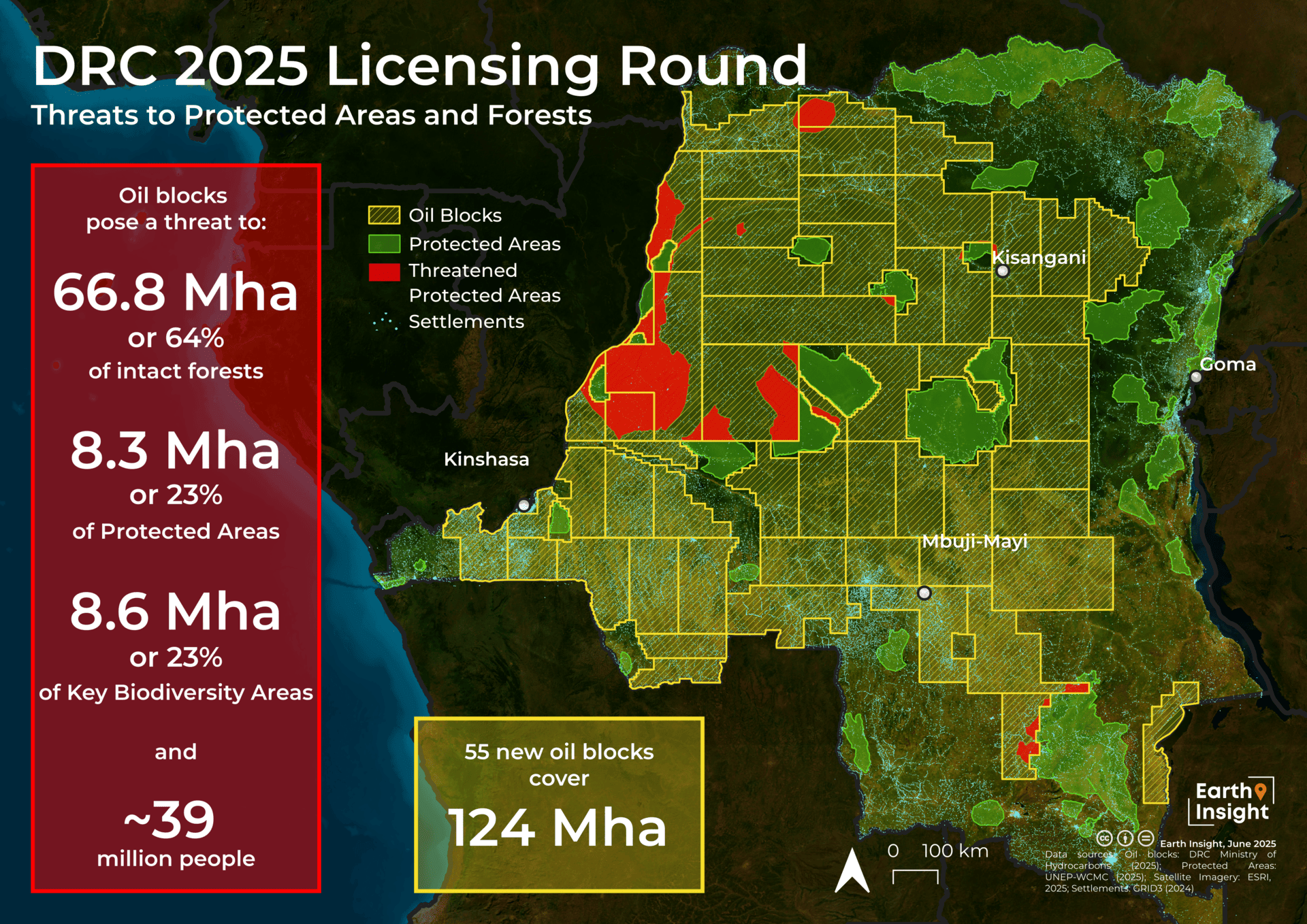

A new report from Earth Insight and partners reveals that the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) recently approved tenders for oil development across more than half the country, launching a new licensing round for 55 oil blocks—52 newly announced in 2025 and three previously awarded.

This new report, in partnership with DRC-based groups Our Land Without Oil and CORAP, as well as Rainforest Foundation UK details dramatic expansion of extractive activities that pose major threats to forests and protected areas that are critical to the health of communities and the planet.

- Oil blocks overlap with 8.3 million hectares of protected areas (23%), 8.6 million hectares of Key Biodiversity Areas (23%), and 66.8 million hectares of intact tropical forests (64%).

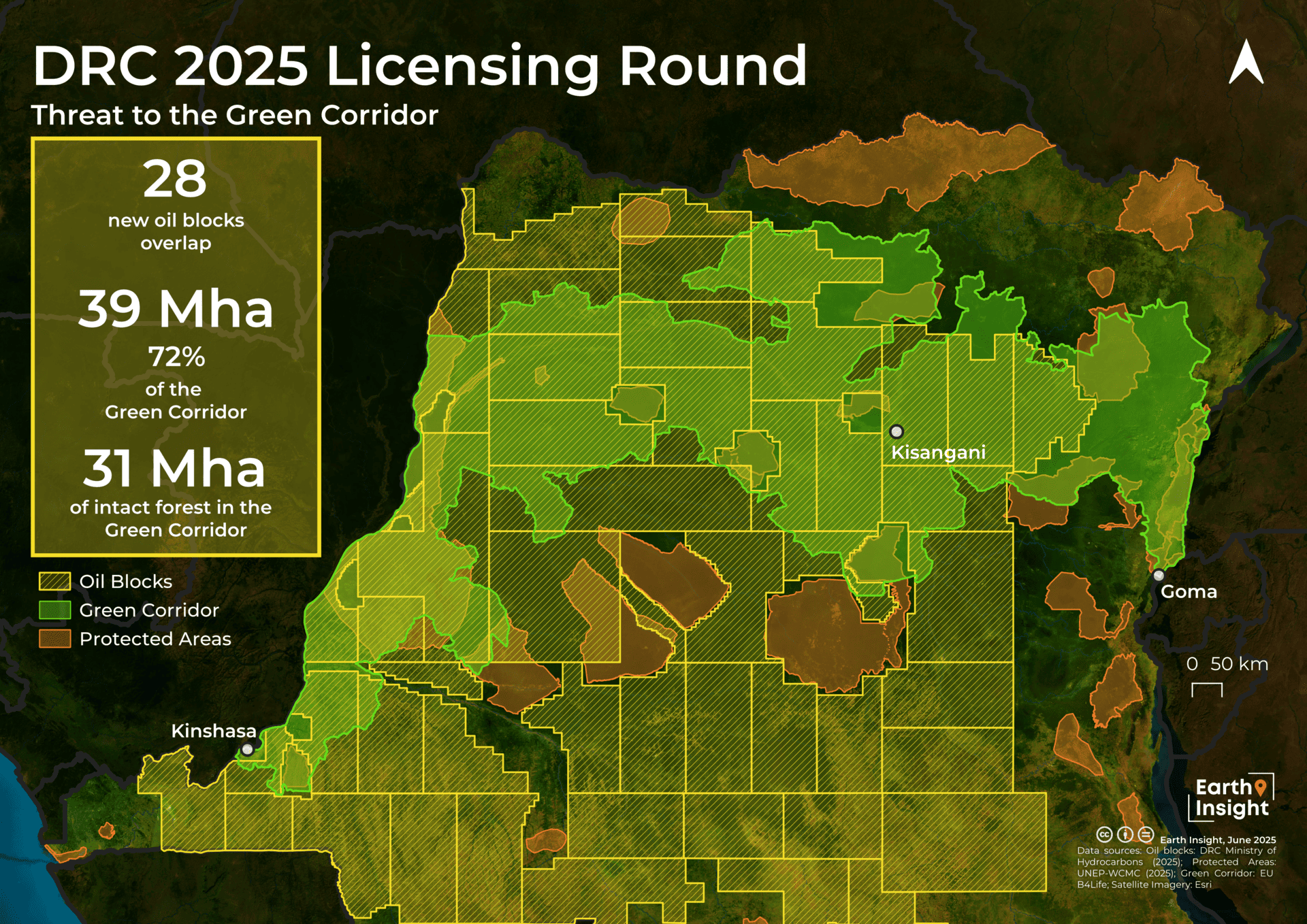

- 72% of the newly established Kivu–Kinshasa Green Corridor, a flagship conservation initiative announced in early 2025, is now overlapped by oil blocks, jeopardizing its ecological integrity and undermining its credibility as a sustainable development and climate solution.

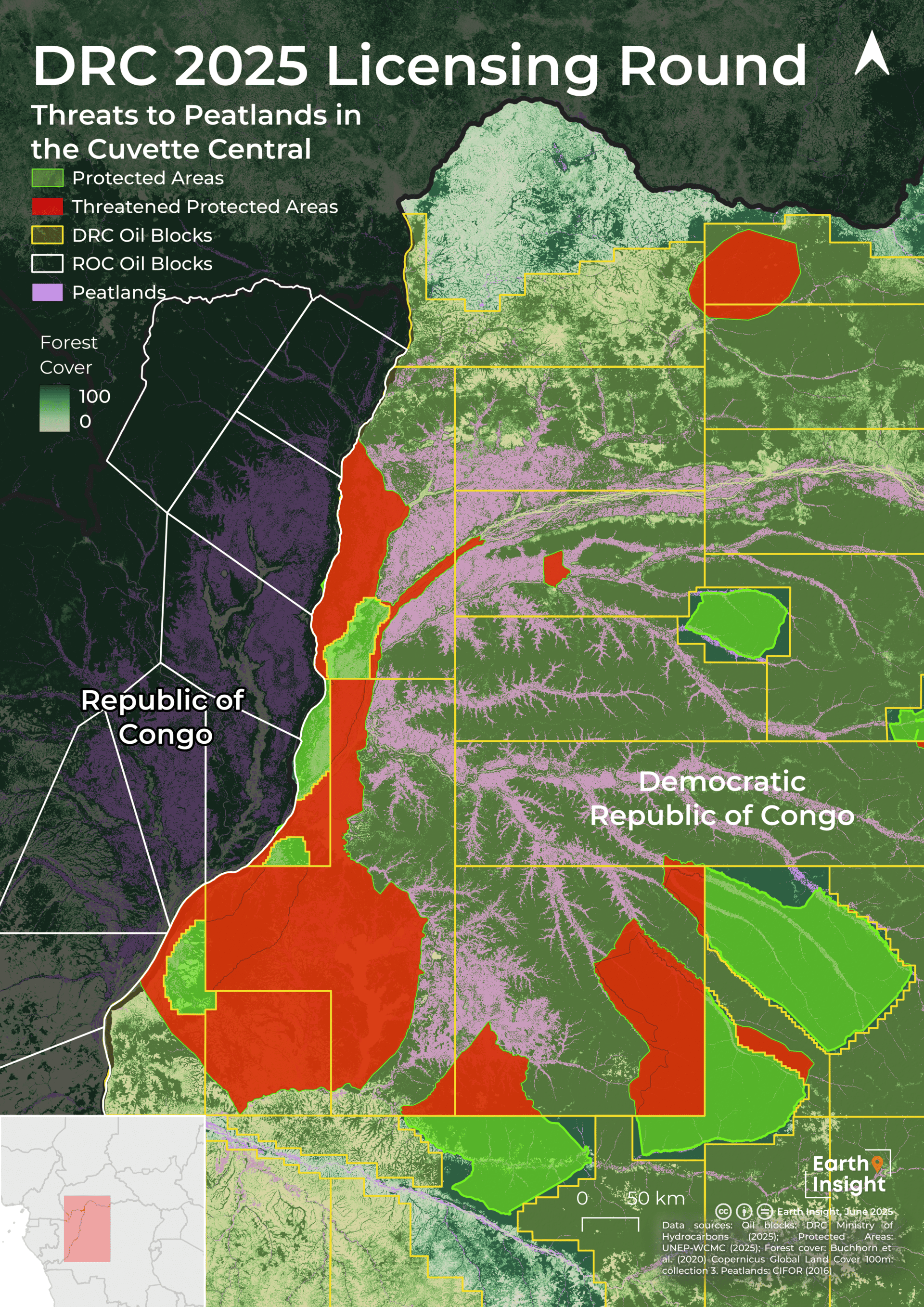

- The Cuvette Centrale, the world’s largest tropical peatland complex and a crucial carbon sink storing an estimated 30 gigatons of carbon, is at serious risk of degradation, with the majority of the DRC’s peatland area now included in newly designated oil blocks.

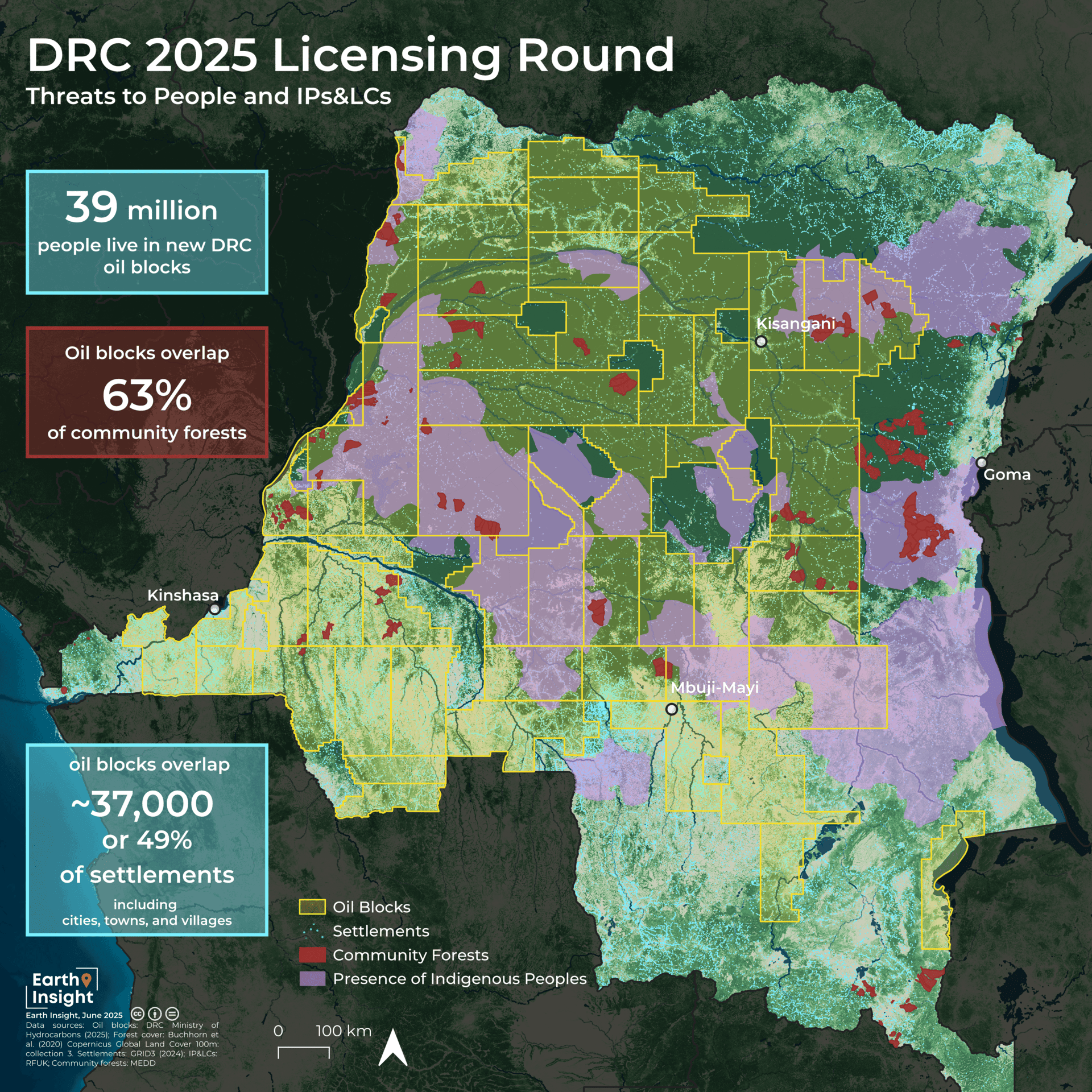

- An estimated 39 million people live within the new oil blocks, which overlap with ~37,000 or 49% of the DRC’s settlements.

- 63% of community forests are overlapped by oil blocks , which represent critical ecosystems for the livelihoods, cultures and survival of many Indigenous peoples and local communities.

Towering rainforest canopies, winding river systems, and vast carbon-rich peatlands make the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) one of the most ecologically significant places on Earth. Home to the second-largest tropical rainforest on the planet, the DRC harbors an astonishing wealth of biodiversity including elephants, great apes, endemic birds, and thousands of plant species that thrive in its intact ecosystems. Its Cuvette Centrale peatlands store massive amounts of carbon, critical to fighting climate change. The landscapes that form this rich mosaic of life are also a lifeline for millions of people, supporting local livelihoods, cultural identity, and climate resilience.

Our Land Without Oil protest in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Courtesy of Notre Terre Sans Pétrole

The ecological health of the DRC is deeply intertwined with the health of the planet, playing an outsized role in regulating the global climate and preserving biodiversity. Yet despite strong national and international opposition, the DRC has continued to pursue fossil fuel development across ecologically sensitive areas. In 2022, the government launched a controversial auction for 30 oil and gas blocks, many of which overlapped with protected areas, peatlands, and Indigenous and local lands. The move, which was covered in a previous report by Earth Insight and RFUK, drew widespread condemnation for its potential to accelerate deforestation and disrupt globally important carbon sinks. Following strong national and international opposition, the Ministry of Hydrocarbons announced the partial cancellation of that auction in October 2024, removing several blocks.

Now, the government has launched a new licensing round for 52 oil blocks, in addition to three previously awarded. This latest round spans an unprecedented 124 million hectares of land and inland waters, a dramatic expansion from the controversial 2022 auction. Many of the proposed blocks encroach upon protected areas, lands inhabited by Indigenous people and forest-based communities, primary and intact forests, peatlands, and other high-integrity ecosystems that are essential to biodiversity conservation, climate stability, and local livelihoods. The move directly threatens the country’s conservation goals and undermines its global commitments to climate action and the protection of biodiversity.

The Expanding Reach of Oil Concessions in the DRC

The DRC’s new oil licensing round calls into question the country’s stated commitment to environmental protection and social progress. Rather than steering away from fossil fuel expansion, the government has dramatically widened the reach of oil concessions, putting at risk the ecological integrity of the Congo Basin. More than half of the country (53%) is now covered by oil blocks, threatening vast areas of ecological importance, disrupting local livelihoods, and threatening lands of cultural and spiritual significance, undermining the country’s potential for sustainable development.

Oil wells in operation on the outskirts of Muanda, on the southwestern tip of the Democratic Republic of Congo. Image credit: Alexis Huguet/AFP via Getty Images

Conservation Wins Eclipsed by Expansion

The 2025 licensing round includes a few notable, although limited, conservation wins. Several high-profile protected areas were removed from concession boundaries following sustained pressure from civil society and international environmental defenders. Among those spared is Virunga National Park, a UNESCO World Heritage Site that faced significant overlap with oil blocks in the controversial 2022 oil block auction.

However, this apparent victory masks a more disturbing reality. The new oil blocks still overlap with 8.3 million hectares of protected areas (23%) and 8.6 million hectares of Key Biodiversity Areas (KBAs) (23%): sites identified as globally significant for species and ecosystems. These overlaps risk legal, ecological, and social conflict and threaten the integrity of places meant to be safeguarded for future generations.

The Green Corridor Project Undermined by Oil Licensing Round

Formally established by ministerial decree in January 2025, the Kivu–Kinshasa Green Corridor aims to sustainably manage 540,000 km² of land and water in the Congo Basin. This vast area the size of France forms a connective spine between the east and south-west of the country, linking biodiversity hotspots and carbon sinks in an ambitious attempt to safeguard ecosystem integrity at the landscape scale. The announcement of the Corridor drew significant praise from Congolese environmental groups, international conservation organizations, and donor institutions, many of which heralded it as a breakthrough for large-scale conservation and sustainable development in the Congo Basin. In theory, the Green Corridor could help DRC meet its commitments under the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, REDD+ agreements, and the Paris Agreement, while simultaneously positioning the country as a global leader in rainforest protection.

Just months after its formalization, however, the integrity of the Green Corridor project is being called into question by the latest licensing round the DRC. 28 oil blocks representing 39 Mha overlap with the Green Corridor, representing a striking 72% of the Corridor’s area. This overlap threatens to compromise the very ecosystems the project is intended to protect, including critical habitat for endangered species, peat swamp forests, and intact forest landscapes essential for carbon storage. If developed for oil production, this would introduce heavy infrastructure, pollution risks, and fragmentation into what was envisioned as a contiguous corridor of ecological resilience.

The overlap between these oil blocks and the Green Corridor sends a troubling signal. While the DRC government has touted the ambitious Green Corridor project as a model of environmentally friendly economic development for local communities, the contradiction weakens confidence in the project’s objectives and casts doubts on the sincerity of the DRC’s climate and biodiversity commitments.

Fossil Fuel Expansion in the World’s Largest Tropical Peatland

Deep within the heart of the Congo Basin lies the Cuvette Centrale— a vast, swampy expanse of ancient tropical peatlands stretching across the northern DRC and the Republic of the Congo (RoC). Covering over 145,000 square kilometers, an area larger than Nepal, this lowland region is home to the world’s largest and most carbon-rich tropical peatland complex. Beneath its seemingly impenetrable wetlands lies an estimated 30 gigatons of carbon stored in layers of waterlogged organic matter, accumulated over thousands of years. First scientifically confirmed as a massive carbon sink in 2017, the Cuvette Centrale has since become recognized as one of the most globally important ecosystems for climate stability.

This photo taken on October 19, 2021 on the beach outside of Muanda, on the southwestern tip of the Democratic Republic of Congo shows an oil storage facility. Image credit: Alexis Huguet/AFP via Getty Images.

The DRC’s 2025 licensing round includes new oil blocks that span nearly the entire DRC portion of the peatland, putting vast tracts of this fragile ecosystem in direct danger of exploration and drilling. Extractive development in such waterlogged and carbon-rich soils carries catastrophic risk. Disruption of the peat layer through drainage, road-building, seismic testing, or drilling can expose the buried organic matter to oxygen, triggering decomposition and releasing enormous quantities of carbon dioxide and methane into the atmosphere. Once degraded, tropical peatlands are extremely difficult— if not impossible, to restore within human timescales.

The Human Cost of the latest Oil Blocks

The expansion of oil blocks in the DRC is not only a threat to biodiversity and climate stability, it is a direct threat to local people living amidst the potential extractive developments. An estimated 39 million people live within the boundaries of the newly designated oil blocks up for auction, many of whom rely on the surrounding forests, rivers, and lands for food, clean water, livelihoods, and cultural survival. These are not abstract figures: these people are farmers, fishers, hunters, elders, children, and knowledge holders, whose daily lives and long-term well-being are placed at risk by extractive development.

The latest licensing round places 63% of all community forests in the DRC within oil block boundaries. This overlap threatens to displace communities, erode customary governance systems, and reverse decades of progress toward rights-based conservation. It also violates the principles of Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC), which are enshrined in both national legislation and international law and are meant to protect Indigenous and local communities from precisely this kind of imposed development.

Yaekama, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Image credit: Axel Fassio/CIFOR (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

This report offers a new spatial analysis of the 2025 oil block licensing round, situating it within the broader historical context of proposed fossil fuel development in the DRC. It also elevates the growing chorus of opposition from civil society, community leaders, Indigenous Peoples, environmental defenders, and scientists to oil and gas activities in such critical ecosystems and climate strongholds. Their message is clear: large-scale fossil fuel expansion in ecologically important landscapes is incompatible with a livable future for people and the planet.

Key Solutions and Proposed Actions

• In line with the demands of Congolese Civil Society, cancel the 2025 oil block licensing round and stop all future hydrocarbon expansion.

• Treat the Cuvette Centrale peatlands as a non-negotiable conservation priority.

• Revoke oil blocks that fall within the Kivu–Kinshasa Green Corridor.

• Respect and uphold the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities.

• Recognize and protect community forests and customary lands yet to be formalized from industrial expansion.

• Advance key legal and policy reforms such as implementation of the Indigenous Peoples and land-use planning laws and development of a new national community forest strategy.

• Accelerate progress towards low-carbon development.

• Align international financing and donor support with climate, biodiversity, and rights commitments.

• Guarantee meaningful participation and transparency. Involve communities and civil society in environmental governance, monitoring, and decision-making processes.